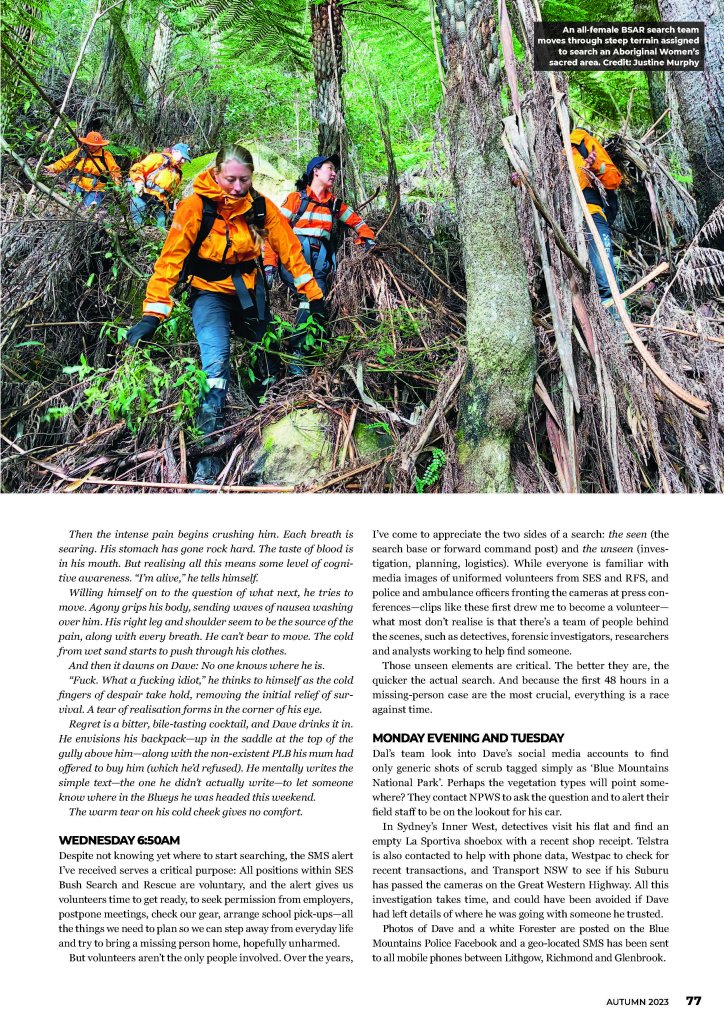

The Anatomy of a Search

This story is a work of fiction, based on my 19 years of actual search jobs with NSW SES Bush Search and Rescue (BSAR), formerly Bushwalkers Wilderness Rescue Squad. It first appeared in Wild Magazine #187 Autumn 2023.

Saturday 8.38 am

The headlights of the Forester worked hard to cut through the mountain mist as Dave turned off the bitumen towards a lightening sky.

Dropping his speed to avoid kangaroos and potholes, the moment brought back memories of long-past adventures, before the claustrophobia of pandemic restrictions and bushfires had forced him inside. This was it – he needed to get out.

Pushing further away from the city in his mind, he passed the patchwork quilt of radiata pine in the State Forest, making several turns along logging trails, before crossing the invisible boundary into the national park. It was years since he’d been out here and although things didn’t exactly reflect his memory, he put it down to newer or re-routed roads due to forestry, along with the fog of years.

Forty minutes along the dirt, he came to a barrier, standing proud in an attempt to stop 4WD weekend warriors from chewing up the park. ‘It’s no wonder the trip took longer than I remember given the state of the road’, he thought to himself. He didn’t remember the barrier being there, but hey, a lot can happen in five years.

He peeled himself out of his car, body stiff from the long drive and breathed deeply. Turning to face the light, he closed his eyes and felt the rising sun’s warmth on his face. A kookaburra’s call broke the silence. This was going to be an epic weekend.

Wednesday 6.45 am

I know it’s bad to check my phone first thing every morning, but I can’t help it – it’s a habit – borne from 19 years as a volunteer in land search where most of our call-outs come on Tuesdays or Wednesdays.

This particular Wednesday met those expectations – a missed call from Sergeant Dallas Atkinson from Blue Mountains Police. Dal, the Co-ordinator of Police Rescue, who has been wearing the white overalls for 16 years, had rung with a heads-up on a search for a missing bushwalker in the Blue Mountains. It’s here that I’m responsible for the 45 volunteers—all positions within SES Bush Search and Rescue are voluntary—between the Nepean River and the South Australian border in Bush Search and Rescue (BSAR), a specialist unit within the NSW State Emergency Service.

My heart quickens as my waking eyes struggle to focus. An early morning call from Dal means one thing: there’s a job on. In an instant, my plans for the day disappear and I sigh, “Here we go again.”

I blink while a million thoughts scroll past my mind: a priority list of questions and logistics, procedures and policies. Behind each one, the shadow of humanity, a name, a story and a family I’m yet to be introduced to.

Quickly scrolling through my notifications, I find what I’m looking for: an SMS from the rostered BSAR Duty Officer sent via SES software called Beacon. This web-based app registers all jobs that come through the SES call centre in State HQ, along with direct messages from other emergency services via ICEMS (Inter-CAD Electronic Messaging System).

The message reads:

“BSAR STANDBY BLUE MTS and GREATER SYDNEY, search for missing bushwalker Blue Mts. Reply if available next 3 days to Duty Officer. Overnight SOPs, day search also available. Standby for activation.”

Saturday 9.50 am

Dave stepped away from his car and pushed into the scrub – it was thicker than he expected.

Before the chorus of his ear-worm song, Queen’s ‘Under Pressure’, had finished, he found what he thought was the spur leading down into the exit of the canyon he’d done with Matt and Phil 5 years ago.

Now, he was looking for the spot where they’d found a huge island slab of sandstone, framed by banksias, that glowed orange under the setting sun. It was here they sat, shared a joint and watched Venus appear. The three talked about their hopes, dreams and everything that was to come after their upcoming uni graduation. It was a spot Dave had long said he wanted to return to and bivvy for a night.

He’d been going for what felt like a couple of hours; without a watch, it was hard to tell. Surely, that rock slab was somewhere around here? He pressed on, regardless of the rising, niggling doubt that was starting to lurk in his stomach. Pushing it away, he chose to focus on the joy of being in the bush and told himself he’ll come across it soon.

Hearing the sound of singing water below and keen to fill his water bottle, he paused in an open saddle before heading down into the gully.

“Maybe after a break things will start to be clearer and I’ll be able to work out where I am”, he thought.

As his eyes adjusted to the dense canopy, he was struck by the beauty of this hidden world: The transition from classic dry sclerophyll forest to Coachwood-topped rainforest, laden with a rich green filter. He grabbed hold of trees to steady his descent and a few drips from the previous night’s rain hit his face.

He takes a step, avoiding the moss-covered rock, and chooses a wet, grey boulder – it moves – and Dave is instantly propelled, pinball-style, down the narrow, steep gully.

Spurred on by gravity, he tumbles and bounces the way bones and flesh aren’t designed to. Ragdoll limbs try in vein to arrest his fall, only managing to nudge more rocks and vegetation along for the wild ride. The sound of snapping registers as branches – not the bones that they are – and random memories of being on the rotor at Luna Park flash by, all driven by a sound track of Queen and David Bowie. Under pressure…

Suddenly, there are no more rocks and he is free-falling, past the life-giving waterfall he was seeking out.

Monday 3.46 pm

The phone rang at Katoomba Police Station.

“Hey, umm, I’m a bit worried about one of my employees, Dave Gill. He hasn’t shown up for work today and I’ve tried to call him three times. The thing is, this just isn’t like Dave – he’s super reliable, always on time. He told us he was heading up to the Blue Mountains for a hike and I can see some shots on his Instagram account from Saturday morning, but now I haven’t heard from him. I thought I’d contact you guys to see if you’d heard anything.”

Dal and the team at Katoomba Police start work by contacting Dave’s next of kin from his HR records. Unfortunately, his mum hadn’t spoken to him in over a week and didn’t even know he’d gone to the Mountains. She gave them a name of a mate he’d been canyoning with before, back in his uni days.

The Blue Mountains are represented on Google Earth by a massive, brooding slab of dark green. Sending volunteers out now would be a search for the proverbial needle in a haystack.

There’s no point in activating a search without a Last Known Position (LKP) – from where all searches begin – as well as determining if Dave was indeed, missing.

Wednesday 6.50 am

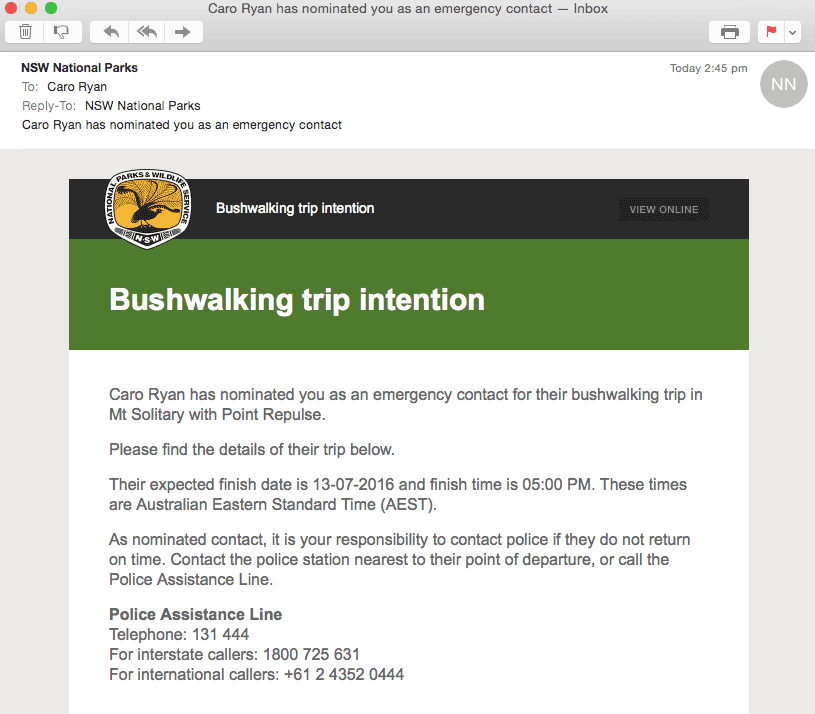

Despite not knowing yet where to start searching, the SMS alert I received serves a critical purpose for volunteers. It gives us time to get ready, seek permission from employers, postpone meetings, check our gear and arrange school pick-ups – all the things volunteers need to plan so we can step away from everyday life and try to bring a missing person back home, hopefully unharmed.

Saturday 11.10 am

Dave hits the deck. Oomph – A small beach at the base of a waterfall.

Blinking away grit and dirt, he struggles to open his eyes and tastes blood in his mouth. Face up in coarse sand, he turns his head slowly to see an image of intense beauty: a lost mountain cascade, tumbling humbly over a four-metre waterfall. Is this life or is this heaven?

The pain is intense – each breath searing – and his stomach has gone rock hard.

“I’m alive,” he tells himself, realising this means some level of cognitive awareness. “Fuck. I’m alive.”

Willing himself onto the question of what next, he tries to move, feeling the cold from wet sand starting to push through his clothes.

Agony grips his body, sending waves of nausea washing over him. His right leg and shoulder seem to be the source of the pain, along with every breath. He can’t bear to move.

It’s at that moment he realises no one knows where he is.

“Fuck. What a fucking idiot,” he thinks to himself as the cold fingers of despair begin to take hold, removing the initial relief of survival. A tear of realisation forms in the corner of his eye.

Regret is a bitter, bile-tasting cocktail. At that moment, he drinks it in with images of his backpack – up in the saddle at the top of the gully above him, along with the non-existent PLB his mum had offered to buy him (which he’d refused) and for not sending a simple text to let someone know where in the Blueys he was headed this weekend.

The warm tear on his cold cheek gives him no comfort.

Over the years, I’ve come to appreciate the two sides of a search: the seen (the search base or Forward Command Post) and the unseen (investigation, planning, logistics).

Everyone is familiar with media images of uniformed volunteers from SES and RFS walking into the bush and Police and Ambulance officers fronting the cameras at a press conference. It was clips like these that first drew me to become a volunteer – to try to help.

But what most don’t realise is the team of people behind the scenes, such as detectives, forensic investigators, researchers and analysts working to help find someone. And because the first 48 hours in a missing person case is the most crucial, everything is a race against time.

Monday and Tuesday

Dal’s team look into Dave’s social media accounts to find only generic shots of scrub tagged as simply ‘Blue Mountains National Park’. Perhaps the vegetation types will point somewhere? They contact NPWS to ask the question and to alert their field staff to be on the lookout for his car.

In Sydney’s inner west, detectives visited his flat and found an empty La Sportiva shoebox with a recent shop receipt.

Telstra was contacted to help with phone data, Westpac to check for recent transactions and Transport NSW to see if his Suburu had passed the cameras on the Great Western Highway. All this investigation takes time and could have been avoided if Dave had left details of where he was going with someone he trusted.

Photos of Dave and a white Forester were posted on the Blue Mountains Police Facebook and a geo-located SMS had been sent to all mobile phones between Lithgow, Richmond and Glenbrook.

Amongst it all, big questions are asked long before conspiracy theorists and keyboard warriors do. Is he even lost? Is he a criminal? Was he the victim of crime? Did he want to disappear? Did he even want to be found?

Monday 5.05 pm

Dave is dreaming. In his mind, where pain is suspended, he is with Matt and Phil, soaking up rays on the rock slab and riffing about life. The bass line of Queen’s Under Pressure is becoming louder and louder, rhythmic, like the beating blades of a helicopter.

A helicopter.

He urges himself further away from the water’s flow, higher up to dry sand, where the leeching contact of damp won’t draw his life away.

Wednesday 7.10 am

As I throw the last things into my backpack, my phone comes alive again with another SMS. Finally, we’ve got a starting point – Dave’s LKP – and we can make our way to a rarely used fire trail which will act as our staging area and forward command post.

Luck seems to play a part in these things – it did for Dave… He bought fuel at BP in North Richmond and the detectives verify it was him in the CCTV, while his Forester was sitting outside. This meant that the tiny window of clear skies could focus Polair’s airtime to several passes around the Newnes Plateau – areas that his old canyoning mates had told Dal’s colleagues about.

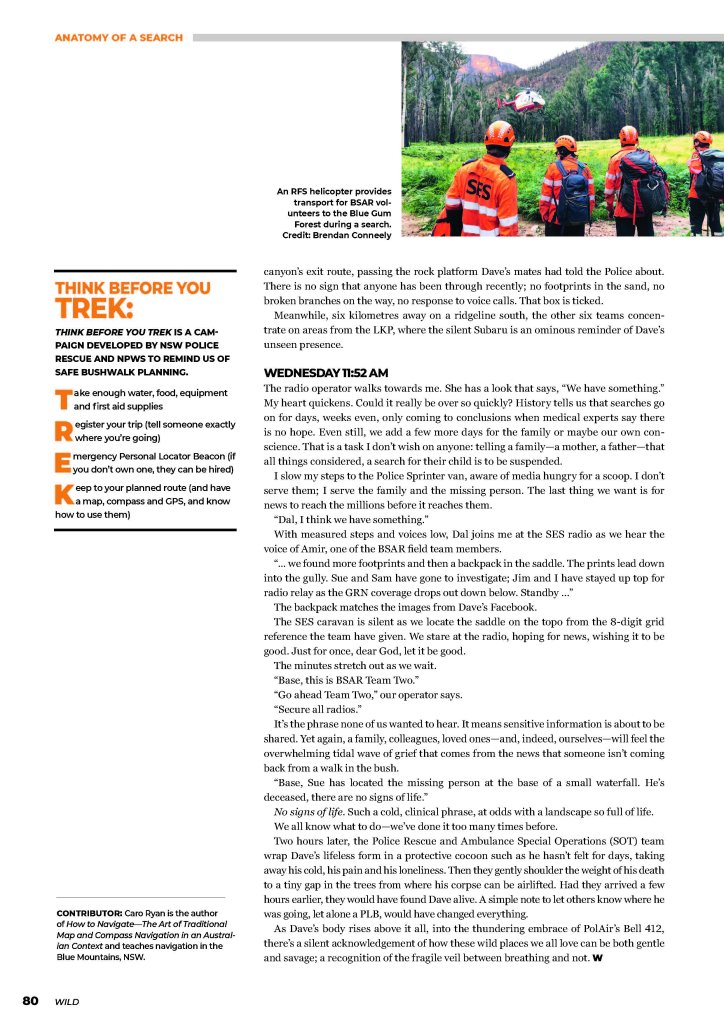

Sure enough, at the end of a long fire trail, the aircrewman spotted a white car and through the high-powered nose-mounted camera, he verified the rego plate of Dave’s Forester. Minutes later, the low cloud rolled in again and Polair needed to return to Bankstown. It was up to boots on the ground to find him now.

Within 45 minutes, two constables from Katoomba Police Rescue arrived at his car and began searching. They pushed into the scrub, following a fresh set of La Sportiva tracks for about 300m before they disappeared.

Like shutting down a computer, I check out of my life – my work, my family, my friends – and I feel the steely, blinkered focus that comes as I put on my SES uniform. I no longer serve clients, deadlines or self; I serve Dave, his family and the NSW Police.

I drive to the search location in one of two BSAR Hilux’s. It’s crammed with gear essential for any bush adventure, plus a few extra things that make a searcher’s pack a little heavier than a normal weekend trip: packs, rain jackets, SES radios, HF radios, InReaches, GPS units, PLBs, hand lines and meal ration packs.

Wednesday 8.30 am

I slow down as I approach the command post – like clockwork my heart quickens. It doesn’t matter how many times I’ve done this, but I feel uneasy knowing that this is the worst day in someone else’s life. How can I begin to conceive what his family is going through? His mates? Himself, if he is even still alive for such thoughts?

We’re lucky at this location – we have patchy 4G coverage. It’s not uncommon to have to request communications support from an SES CoW (Cell on Wheels) or SES500 (GRN ‘Government Radio Network) radio repeater. So by the time I pull up, greeted by the familiar blue, red, orange and white of a command post, our Duty Officer (DO) has confirmed we have 12 field team volunteers (3 teams x 4 people) and 2 base members to assist for the day.

There’s a term: Command and Control. It’s the foundation of any emergency services (or military) work. Like an organisation chart, this pyramid-shaped structure helps the effective flow of information and delegation, sets the expectations of everyone involved and when dealing with crisis and operational situations, is essential for an effective process.

On the scene, each organisation has a Commander – an operational role that isn’t necessarily the most senior ranked person – who represents their agency, bringing their unique voice and skills to the planning and execution of the job. They report to the Police Search Coordinator, who is in charge of the operation.

I smile as I walk to greet familiar faces, people I wouldn’t recognise out of uniform. We’re an odd bunch, who can convey a thousand words with the raise of an eyebrow or a piss-take which translates as deep respect and a strange kind of love. We each understand this unusual world we inhabit, which for us volunteers, is one we step into and out of about once a month… we wish it was less.

I enter the Police Command Post to learn that Sergeant Atkinson has several likely scenarios and a list of search taskings, broken down by difficulty, to assign to each agency. Taskings are usually areas bounded by geographical features, like a spur between two gullies, a particular creek or cliff line, allocated to teams with appropriate skill, expertise and fitness.

There is science to this, layered with local knowledge and a fair slab of gut instinct. Missing Person Behaviour data is an area of academic research and just one tool at our disposal. It’s an area that fascinates me and search strategy is one of the tasks I relish the most. Topographic maps are laid out, background from the detectives is shared, and likely scenarios and risks are discussed. These include if Dave was known to be despondent, meaning is there a chance he may have headed into the bush to take his own life.

As volunteers, this can be troubling. We need to ask ourselves, “Am I OK if I find Dave and it’s not a good outcome?” The sad reality is that because of the types of jobs our unit does in the most rugged and remote areas of NSW, the scales are tipped in favour of the dead… we can go years without finding a live one.

As Commanders, we discuss all the data, along with the type of search needed. It could be a rapid reconnaissance search, a slow, detailed forensic search on hands and knees or anything in between.

At 9.30 am, we move outside to brief the search teams from all agencies following a SMEAC (Situation, Mission, Execution, Administration, Command and Communications) template. Part of our briefing includes details of our planned SITREPs (Situation Reports) which each team will need to radio in every hour. These include location, a description of the terrain, % of the tasked area covered, team welfare and intentions.

Tuesday 3.25pm

Dave registers a groan as his own as he tries to move out of another torturous cramp. The aching cold. The searing pain. The relentless optimistic life-filled sounds of the waterfall, oblivious to the life that has been slowly leaving him these last few days. His fingernails dig into the coarse sand, trying to hold on to the present.

It’s starting to get dark again. “Please, not another night,” he weeps, longing for dreams, delirium, death or rescue – all welcome respites from his living hell.

Wednesday 10.42 am

By mid-morning the fast team (who were driven to a different starting point) made it all the way down the canyon exit route, passing the rock platform Dave’s mates had told the Police about. There was no sign that anyone had been through recently, no footprints in the sand of the canyon, no broken branches on the way down and no response to voice calls. That box is ticked.

Meanwhile, 6 km away on the next ridgeline south, the other 6 teams were concentrating on areas from the LKP, where the silent Subaru was an ominous reminder of Dave’s unseen presence. Police had gained access to the car to look for further clues. The petrol receipt and wrappers from packets of food he’d bought, along with track notes he’d printed from a Blue Mountains Hiking Facebook group. In them, someone had posted about an incredible rock platform in the area only a week ago.

Dave has woken to the sounds of distant voices and the unforgiving sing-song of the waterfall. Did he imagine it? He doesn’t know what to believe anymore. What is real, what is imagined. The seasons are messed up: it’s autumn but he’s burning hot as his good arm claws to remove his layers.

He doesn’t know it, but he is hanging on by a thread.

Wednesday 11.52 am

The radio operator walks towards me, raises her eyebrows and motions me to come over. She has that look on her face that says, ‘We have something’. My heart quickens as I draw breath. Could it really be over so quickly? History tells us that searches go on for days, weeks even, only coming to a conclusion when the medical survivability experts say there is no hope… even still, we add a few more days for the family or maybe our own conscience. That is a task I don’t wish on anyone: telling a family – a mother, a father – that all things considered, a search for their child is to be suspended.

I slow my steps to the Police Sprinter van, aware of hungry media eager for a scoop. I don’t serve them, I serve the family and the missing person. The last thing we want is for news to reach the millions before it reaches them.

“Dal, I think we have something.”

With measured steps and voices low, Dal joins me at the SES radio as we hear the voice of Amir, one of the BSAR field team members describing the scene.

“… we found more footprints and then a backpack in the saddle. The prints lead down into the gully. Sue and Sam have gone down to investigate, Jim and I have stayed up top for radio relay as the GRN coverage drops out down below. Standby…”

The backpack matches the images from Dave’s Facebook.

The SES caravan is silent as we locate the saddle on the topo from the 8 digit grid reference the team have given. We stare at the radio, hoping for news, wishing it to be good – just for once, dear God, let it be good… Let the next words we hear be able to hold back the overwhelming tidal wave of grief that washes over a family, over ourselves.

The minutes stretch out as we wait.

“Base, this is BSAR Team 2.”

“Go ahead Team 2”, our operator says.

“Secure all radios.”

I step back, breathe out and look to Dal. It’s the phrase that none of us wanted to hear. It means sensitive information is about to be shared and that yet again a family, colleagues and loved ones will feel the yawning schism from the news that someone isn’t coming back from a walk in the bush.

“Base, Sue has located the missing person at the base of a small waterfall. He’s deceased, there are no signs of life.”

No signs of life. Such a cold, clinical phrase that seems at odds with a landscape so full of life.

We all know what to do – we’ve done it too many times before.

2 hours later, the Police Rescue and Ambulance Special Operations (SOT) team wrap Dave’s lifeless form in a protective cocoon such as he hasn’t felt for days.

Kneeling beside him they take away his cold, pain and loneliness as they gently shoulder the weight of his death to a tiny gap in the trees.

As he rises above it all, into the thundering embrace of Polair’s Bell 412, there’s a silent acknowledgement of how these wild places we all love can be both gentle and savage; acknowledging the fragile veil between breathing and not.