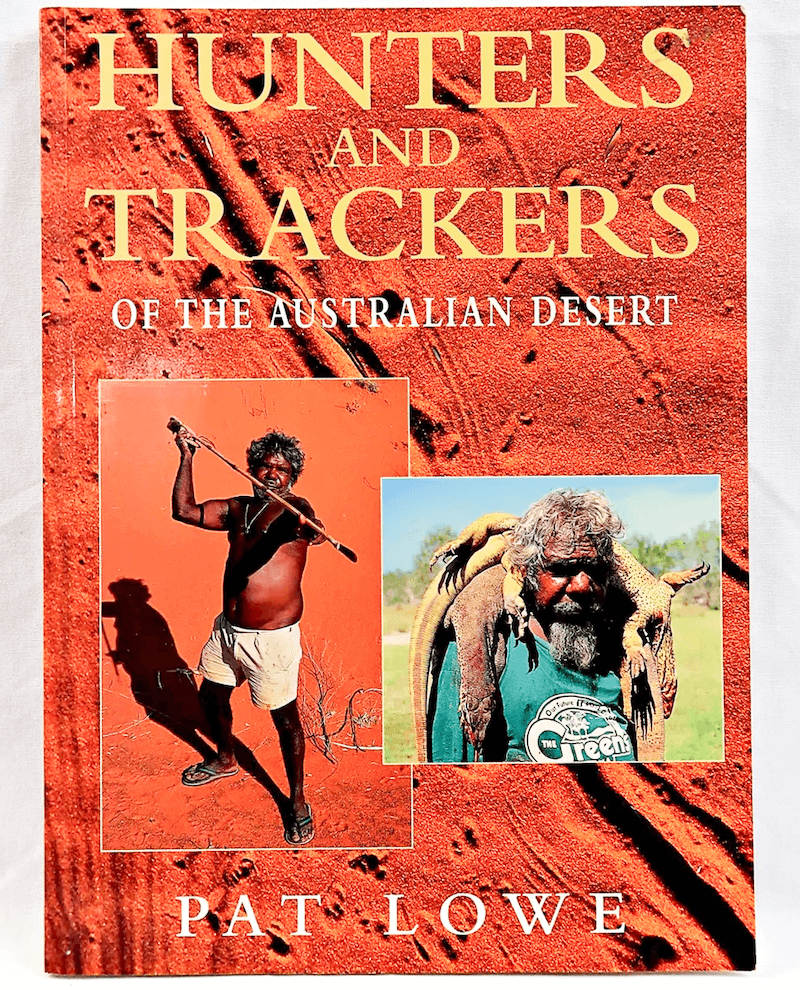

Written by Pat Lowe, this article is an excerpt from her book, Hunters and Trackers of the Australian Desert (Rosenberg Publishing). Now out of print, you may find it on second-hand websites. It appeared in Adventure Journal 2007, edited by Lucas Trihey, and she has kindly granted permission for me to share it here, along with quoting it in the 3rd edition of my book, “How to Navigate” (out July 2025).

About the author

In the late 1980s, Pat Lowe spent three years living in the Great Sandy Desert with her Walmajarri companion, artist Jimmy Pike, who was one of the last people to grow up as a hunter and gatherer in Australia. During that time, Pat learnt about the desert way of life and observed in practice the traditional skills of the hunter.

More than tracks

Desert people, men and women alike, learnt to read tracks: they were able to identify not only the type and size of animal that had made the tracks, but information such as its age and gender. They could tell what the animal had been doing at each stage of its journey: when it had run, walked or stopped, encountered another animal or caught prey, engaged in courtship behaviour, had a feed or gone to sleep.

But, no matter how good your tracking skills may be, they are of little use if, after catching your prey, you can’t find your way home. No hunter would retrace his own tracks. In the course of a day, he goes wherever an animal leads him. He can’t afford to cover all that ground again just to get back to camp.

Are you born with a good sense of direction?

For me, the ability, after hours of meandering, to head off as the crow flies, unerringly back to camp or car, has never lost its wonder. It is not merely a question of knowing a piece of country well, or of taking note of features of the landscape, for people can achieve the same feat in country they have never visited before.

In 1838, when HMS Beagle, under Captain Wickham, was exploring the north-west coast of Australia, a Swan River man named Miago was recruited as gunroom steward and to help make contact with ‘the tribes’. Marsden Hordern, in his account of the voyage, based on the journals of Assistant Surveyor John Lort Stokes, says that Miago “surpassed all the Beagle’s navigators” in his directional ability.

“Far out of sight of land, and under overcast skies, he could point unerringly in the direction of Swan River—information which the Beagle’s officers only acquired after recourse to charts, compass, long line, sextant and chronometer.”

1838 journal, Assistant Surveyor John Lort Stokes, speaking of Swan River man, Miago

It has been suggested that some people inherit a perfect sense of direction, like homing pigeons. This seems unlikely. If some people have it, why don’t we all? And, if you assume that indigenous people evolved this extra sense over several millennia, you must explain its loss by their urban descendants.

I think a good sense of direction is acquired, not inherited. People who live out of doors, constantly aware of the position of the sun and moon, the direction of the prevailing wind, with no maps, roads or man-made signs to rely on, develop a much better sense of space than those who live in towns, with no horizon and little opportunity to observe solar and planetary movements. As small children, city-dwellers are given no information about directions, and when we learn about them at school we do so in relation to a map, not the everyday world. We get around towns by reading the names of streets.

Cities are the one place where desert people become confused. They try to navigate by the sun, but the arbitrary layout of streets and the obscured horizon often defeat them. To desert people, an acute sense of direction is nothing out of the ordinary. Indeed, the loss of the ability to find one’s way is diagnostic of dementia: “He went mad, poorfella,” people say, shaking their heads. “He walked anywhere.”

Whitefella thinking

I used to try to cover up my poor sense of direction just as some people try to conceal their inability to read and write. When, on a long walk in the bush, Jimmy would stop and ask me, “Which way motorcar?”. I’d try to remember where he had been looking just before he asked, and point that way. When we drove along one of the seismic lines and Jimmy pointed to a tree and asked if I remembered once having had dinner there. I would say that I did. The dinner he remembered, with details about the number of goannas, cats or snakes we had killed and cooked that day, may have taken place 10 or 15 years before.

Jimmy found my directional blindness humorous at first and regaled friends with tales about me getting lost. “Ah, poorfella,” they’d say. As the years passed, my baffling failure to demonstrate any improvement became a source of irritation and, finally, just a cross to be borne.

How are Aboriginal children taught navigation?

Desert children learn the meaning of north, south, east and west almost as soon as they can walk. They don’t have direction explained to them formally, but learn through the simplest instructions adults give them every day. A toddler looking for a plaything on the sand is directed to it: “There it is, north of you, north!”

If a billy of water is about to tip over on the fire, someone will call out, “Quick! Move it to the east!”

Where white Australians speak of left or right, black ones speak of north or south. Ask them, “Which way’s east?” and they point without hesitation. They are always spot-on. When I was selecting photos for a book, I asked Jimmy to identify some tracks. He would say: “It’s a cheeky1 snake heading south”. “How do you know it’s heading south?”, I’d challenged him. He laughed and admitted that he was reading the direction from the way the photograph was oriented.

In Walmajarri, the vocabulary of direction is rich and detailed. Each of the six directions - the four cardinal compass points and 'up' and 'down' - has a word stem, which takes a variety of suffixes to give the word precision. There are at least a dozen such suffixes. For example, kakarra means east. Kakarrara means in or around the near east, say within a short walking distance. Kakarrampal means to the east of the speaker but running north-south, and may apply to a road or river, a moving person or flying bird. Other terms, using different suffixes, indicate whether the place or object is near or far, in or out of sight, moving towards or away from the speaker. One word says what in English needs a sentence.

Once I had realised how aware of direction he was, I showed Jimmy a compass. I demonstrated how the needle always swings to the north. He looked at it hard for a moment, then handed it back. “All right for you,” he said. “Blackfellas know which way we’re going.”

How to develop a sense of direction

A good sense of direction depends on acute powers of observation and an excellent memory. As people walk in the bush, they constantly take note of what is around them. If they see a turtujarti tree with gum seeping from its bark or a good crop of nuts lying beneath it, they will remember the tree and come back to it later.

One afternoon, Jimmy and I left the car beside a mining road and went hunting on foot. After two or three hours following tracks, we returned to the car. I felt in my pocket for the key; it wasn’t there. I remembered pulling some dried fruit from my pocket and sharing it with Jimmy; I had probably pulled the key out with it.

“Well,” said Jimmy, “You’ll have to follow your tracks back till you find it.”

Fortunately, he relented and off we set, ignoring our own earlier tracks, straight across country. After some time, without breaking stride, Jimmy nodded at the ground. “There’s your key,” he said, with maddening nonchalance – a single car key lying flat on the sand.

Pat Lowe, Hunters and Trackers of the Australian Desert

On other occasions I left a hammer or a hunting stick under a tree and only missed it later, back at camp. It may have been a month or longer before we next travelled the same way, but Jimmy would remember the very tree where I had left the missing item, and we always found it there.

Another time, our car broke down. For the rest of that day and all the following morning we did all we could to get it going again. After lunch on the second day, Jimmy announced that we would have to walk. We set off with our two dogs, carrying a water bottle and rifle. As soon as the sun went down, cold descended. Had I been alone, I would have had to follow our car tracks back along the road, but Jimmy headed across country. On the way, the dogs killed one goanna and Jimmy killed another. During the night, we stopped to make a fire and cooked them for dinner.

It was hard to leave the fire and get going again. Luckily, there was a full moon, which helped us make our way through the spinifex. We watched it move steadily across the sky. Our joints gave us pain but the cold kept us moving. It was almost dawn when we reached our camp and collapsed thankfully on the ground.

Aboriginal navigation by the stars and sky

The moon was a help to us that night, but people like Jimmy can navigate just as well without it. Having slept under the stars for most of their lives, they are as familiar with the constellations as another person might be with his bedroom ceiling. They know the time of year, and of night, that each constellation appears and use them to find their way across their land.

Pat Lowe, Hunters and Trackers of the Australian Desert

In hot weather, people often travelled by night. If they had a long way to go between waterholes, they carried water. They rested during the heat of the day and travelled in the morning and late afternoon, into the night. Occasionally, they ran out of water and had to resort to extreme measures; thirsty as they were, they would bury themselves in cool sand near the base of a tree, and lie there with only their heads exposed, conserving body moisture, until the heat had passed and they could travel on in the safety of darkness.

When we first lived in the desert, we saw jet aircraft crossing the sky. “That one’s going to Sydney,” Jimmy would say. “That one’s going to Singapore.” Since Jimmy at that time had been to neither Sydney nor Singapore, I took these pronouncements with a grain of salt. Only later, when we looked at maps together, did I realise that his understanding of the relationship between different places extended far beyond the Kimberley and the Great Sandy Desert.

Memory of places and Country

Over three years we explored country that Jimmy remembered from his younger days. He wanted to return to Japingka, the main jila or permanent waterhole of the country belonging to his father and his grandfather. The roads we used were seismic lines: sandy tracks driven straight as spears through the desert. We followed them all, but none went as far as Japingka. In a single vehicle we could go no further and had to give up.

In 1988, a film crew made a documentary about Jimmy, the focus of which, at our suggestion, was a journey to Japingka. We took three four-wheel-drive vehicles, with a helicopter for backup and aerial shots. When the utility carrying the fuel drums became hopelessly bogged on top of a jilji2, the rest of the journey had to be made by helicopter.

Jimmy sits next to the pilot and directs him to fly south. Below stretch parallel ridges of sand as far as the eye can see. Jimmy last walked this land as a boy; he has never seen it from the air. To the untrained eye, it all looks the same. There are no settlements, no mountains, no rivers, no roads. After a long while, Jimmy asks the pilot to change direction a fraction. He studies the country as intensely as a hawk. Again he signals for the pilot to change course. Then – “Over there!” In a moment we see it: Payarr, the site of a story that recurs in many of Jimmy’s paintings. From the air it looks like a miniature Uluru rising from the sands. We land on country that has not been walked for 40 years. Jimmy leads us up the rock as if he had climbed it yesterday. He shows us a cave, so low we would have to crawl to enter it. Here, in another life, Jimmy’s mother slept with him and his little brother on rainy nights.

From Payarr, another five minutes’ flight takes us to Japingka.

Pat’s other books, including those in collaboration with Jimmy Pike, are available at Magabala Books and Backroom Press.

1 ‘Cheeky‘ is a Kimberley Kriol word with a wide range of meanings. In this context. it means ‘venomous’.

2 ‘Jilji‘ is a sand dune. In the Great Sandy Desert the dunes run in regular parallel ridges, sometimes for many kilometres.