Part 1 : from origins to clubs

Hiking and bushwalking is experiencing a renaissance in Australia. Gaining momentum through the growth in MeetUp groups and the spread of social media, many of us are being inspired to take to the bush with a desire to escape our urban jungles. But where did this all start? What people, pioneers and explorers have walked before us, laying the path that we now walk?

For an act as natural as taking a step, it’s hard to imagine that there’s a history and a story to it. But to consider the history of bushwalking in Australia, is to dig into the essence of who we are as Australians.

From our ancient Traditional Owners, purposeful in their nomadic walkabouts, to early colonists discovering what lay just over the hill; from botanists and naturalists fascinated with discovery, to gold miners and treasure hunters in search of relief from poverty; from explorers in search of fame, to a colony and early nation struggling with the stressors of the industrialisation of urban life – we’ve been a land of walkers.

Traditional Owners

To point to the formation of walking clubs in the 1930’s and their first recorded usage of the word, ‘bushwalker’, as a revolution, is to miss the key point that the development of bushwalking in Australia was an evolution.

In the 1800’s the term ‘woods-walks’ was more common, but to fully understand how we arrived at the many forms of bushwalking that exist today, we need to go back to the Traditional Owners, the Aboriginals from many different tribes and nations.

Not only are they our First Nations, they are our First Walkers.

In the 2011 award winning book, ‘The Biggest Estate on Earth’ (Allen & Unwin), keen bushwalker Bill Gammage, charts the changes in the Australian landscape from the arrival of Captain Cook to today. He challenges the mindset that the land the colonists arrived upon was an unmanaged, wild frontier, without order and possessed of impenetrable scrub.

In stark contrast, First Fleeter, Arthur Bowes Smyth explains,

”The fresh terraces, lawns and grottos with distinct plantations of the tallest and most stately trees I ever saw in any nobleman’s grounds in England, cannot excel in beauty those whose nature now presented to our view,”

Bill’s argument is that the bush we walk (sometimes push our way) through today is in stark contrast to the 18th and 19th century landscape.

‘There was much more grass and open forest, and plants were more commonly laid out in mosaics, so that except in the arid zone one habitat did not prevail for too long. There was much less undergrowth (scrub), as because it can lift cool fires from ground to canopy, it is a most deadly fire layer. Mosaics and fire made patterns – parks. Most walking tracks large and small were kept clear too.’

Bill Gammage, The Biggest Estate on Earth (Allen & Unwin)

He quotes John Hunter, Admiral, Governor and Explorer (1737–1821), who testifies that the local Aboriginals create tracks with fires “intended to clear that part of the country through which they have frequent occasion to travel, of the brush or underwood, from which they, being naked, suffer very great inconvenience.”

As the colony grew and pushed further and further inland and the Traditional Owners longheld practices of fire management diminished, the “narrow lanes, or openings which the Natives had burnt… through which we could not have pushed but for the narrow lanes made in them by the Natives”, as experienced by Charles Sturt in 1838, started to retreat.

The Explorers

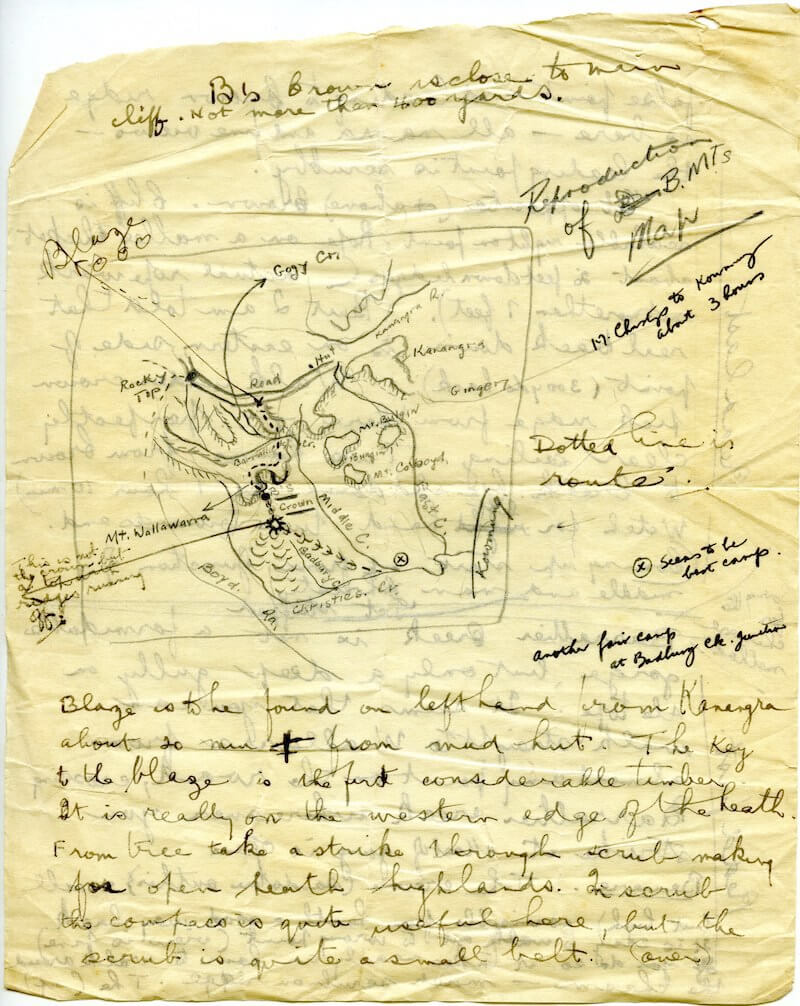

In Melissa Harper’s excellent book, ‘The Ways of the Bushwalker – On foot in Australia” (University of QLD), from which much of the research for this article is based, she points to the purpose of why people were drawn to walk as key stages in the evolution of bushwalking.

Whereas vagrants in England and the early colony walked in their poverty, the upper classes enjoyed a stroll on their estate for hunting or exercising their interest in botany.

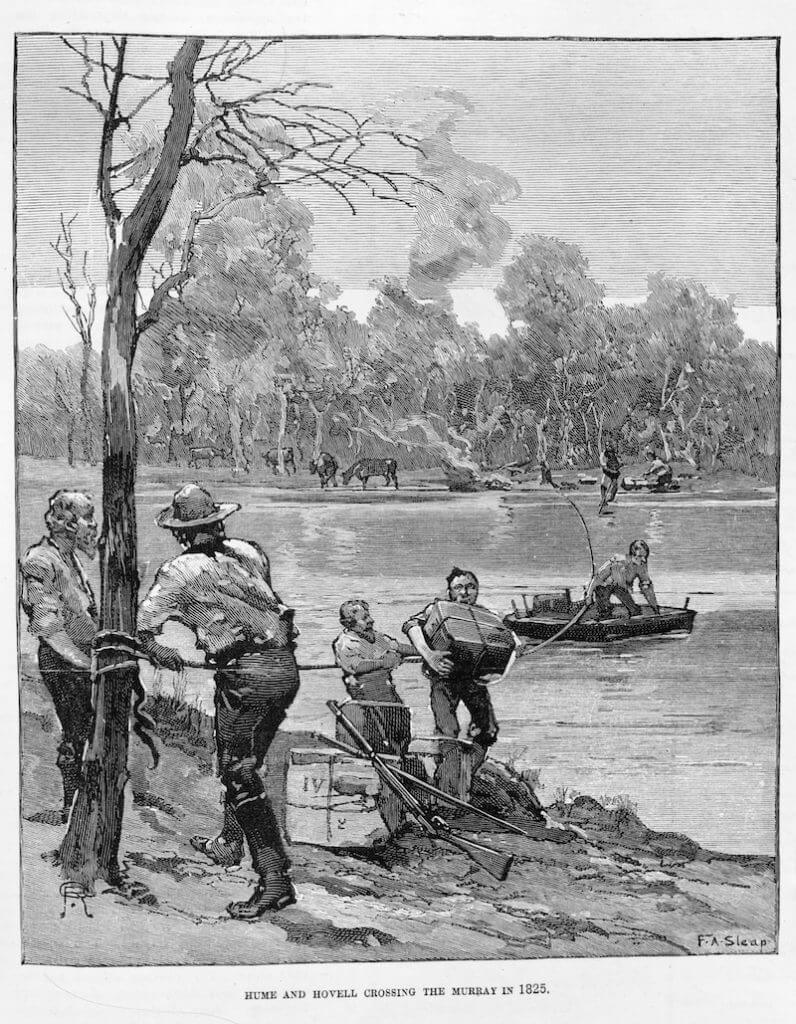

In Australia, the curiosity of the early settlers led some of them to venture not too far from home, but it was the Explorers who took up this curiosity, loaded it with necessity and the chance at heroism, to find ways for the colony to expand.

Funded by the Crown, these expeditions were work, with a set purpose of not only improving life in the new colony (such as finding agricultural lands or inland seas), but in some sense, by seeing the land, have a sense of understanding it and claiming it for the King.

These men were not only adventurous types, but were doing their bit in expanding the British Imperialist stage of the Empire.

Their names are familiar to Australians: Sturt, Hume & Hovell, Leichhardt, Burke & Wills and Blaxland, Wentworth, Lawson all pushed further than any European had.

Not only did they feel that they were going where no white man had been before, but they were free to exercise that very human trait of curiosity, challenge themselves physically and mentally (for some like Burke and Wills to the point of death), for the chance of gazing on unseen sites, being hailed a hero and completing a task.

The Adventurers

When in 1889, Ernest Giles declared himself the last explorer, he saw the door closing on the glorious expeditions of the previous fifty years.

Whereas necessity, ambition and unknown frontiers had previously driven the need for exploration, the 1870s – 1880s were marked by the rise in a new type of curiosity.

They were no longer journeys into the unknown, but long passages between two known settlements or towns, like Huonville to Port Davey in Tasmania. What makes these trips unique, is that there was an alternate and much simpler route by sea, yet our walkers of the day made the choice, to go on foot, often through unknown and difficult terrain.

These adventurers, Piguenit, Johnston, Scott and McPortland, justified their trips to the curious as officially, they were on business. They weren’t simply walking, for walking’s sake. With journeys of 4-6 weeks, carrying 50-70 lb (22-32 kg packs), they were keen to point out that their ‘expeditions’ were more than a tourist jaunt for the lighthearted.

But apart from needing to travel for work, what else would have spurned these men on? Perhaps the call of adventure itself was allowing these men (and others like them) to tap into a part of themselves that the post Industrial Revolution urban lifestyle had started to suffocate?

The benefits (and devices) that industrialisation brought made certain parts of our lives easier, yet changed things forever. Apparently these modern marvels would give us more leisure time. Could this not be said for the internet and our lives today?

The Tasmanians were not alone in their adventurous journeys. Across the strait in Victoria, it was people like Fred Eden and George Morrison who also started to see the joy in walking great distances.

Eden, seeking a tough challenge in isolated country, decided that walking from Melbourne to Sydney would be just the ticket. Morrison tapped into his middle class private school, ‘boys own adventure’ dreams, inspired by his hero Stanley (of Dr Livingstone fame) for his 1882 journey, tracing the steps of Burke and Wills, from the Gulf of Carpentaria to Melbourne.

Melissa Harper’s insight into the space that Morrison occupied is poignant.

“Morrison was forced to straddle the divide between exploration and bushwalking, too late for one, too early for the other.”

The Romantics

If the adventurers and the explorers had an element of conquering about them, attached to the physical realm, the next types of walkers were much more attuned to their own internal world.

Bohemian Sydney of the 1890s was home to writer, poet and friend of Henry Lawson, John Le Gay Brereton. For him, time spent in the bush with his friends was about the sense of freedom and his place within it. His experiences were those of a deep love of the bush, a sense of the spirituality or divinity of all things (Pantheism) and recognising the sensual nature and beauty of the Australian bush.

With walks in Tasmania, along with much time spent in the Blue Mountains, he described his journeys as ‘purposeless rambles’.

It was around this time that a name familiar with many in Australia, also discovered a love for walking this land. Percy Grainger, pianist and composer, was, amongst other descriptions (that were not always complimentary) an avid walker. But in contrast to Brereton’s gentle rambles, Percy seemed to use the physicality of walking, especially at a fast pace, to somehow subdue his body and prime himself for performance. It would not be unusual for him to walk 65 miles to or from recitals.

Both of these men, inspired by the writings of US poet, Walt Whitman, expressed their feelings of the bush through their works.

“Walking emerged as both an external physical experience and an internal quest for meaning, and the two were integrally connected.”

Melissa Harper

The Thinkers

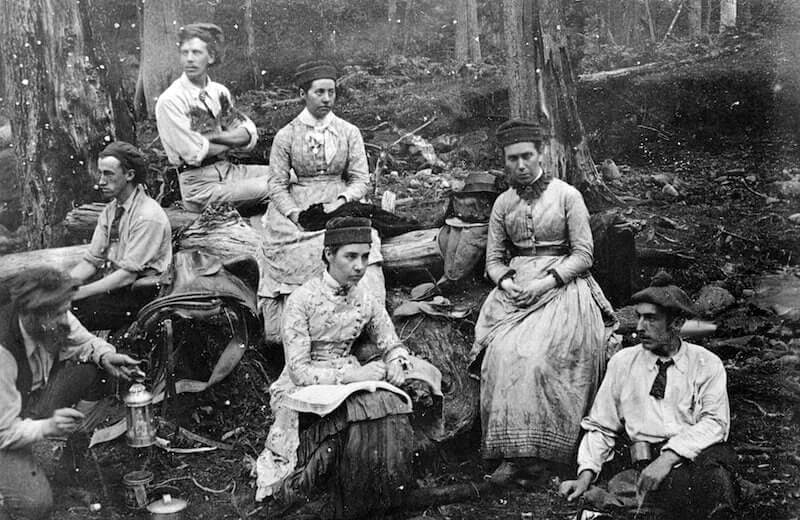

In the post Gold Rush boom of the 1870s a new type of walker emerged – the bush philosopher. Not satisfied with merely walking for the pleasure of the fresh air, away from those dirty built-up cities we were creating, these educated intellectuals, like Alexander Sutherland from Melbourne, walked to aid thought.

For him and his friends, spending time walking in the bush (or forest as he called it) around Healesville and The Black Spur was a chance to ponder, discuss and philosophise about the issues of the day. Whether it be politics, economics or the bigger questions of life, Sutherland’s published essays of trips, suitably vague in detail, were laden with a search for meaning.

It was from this broad church of thoughtful walkers, that the co-founder of Australia’s first bushwalking club emerged. William Hamlet, a scientist, who emigrated to Australia for health reasons, certainly found what he was looking for. Described by the Sun newspaper as ‘one of the world’s most enthusiastic walkers’, he undertook ‘walking tours’ over 500 kms in distance on a somewhat regular basis.

Following in the now grand tradition of reporting one’s adventures, Hamlet took to the pen to describe in detail his adventures on foot, where his focus was more on describing the world outside of himself, than the inward looking romantic. Through his writings he invited readers of the Sydney Morning Herald to see the significance in Aboriginal culture and history, as a way of interpreting our place in Australia.

The Clubs

For many casual observers of the Bushwalking ‘movement’ in Australia, it is easy to assume that our history started here, about the end of the 19th century when walkers of the day followed suit from other hobbyists and started to organise themselves into clubs.

The YMCA Ramblers were the first to kick things off in 1889, however it wasn’t until Melbourne’s Wallaby Club and the Melbourne Amateur Walking and Touring Clubs (MAWTC) were formed in 1894, followed by Sydney’s Warragamba Walking Club in 1895 (founded by John Le Gay Brereton and William Hamlet), that things really started to get on a roll.

As each new club emerged (often from members of existing clubs who saw a better or different way of doing things), the nuances of different walking styles and habits started to gather like minded sorts around them.

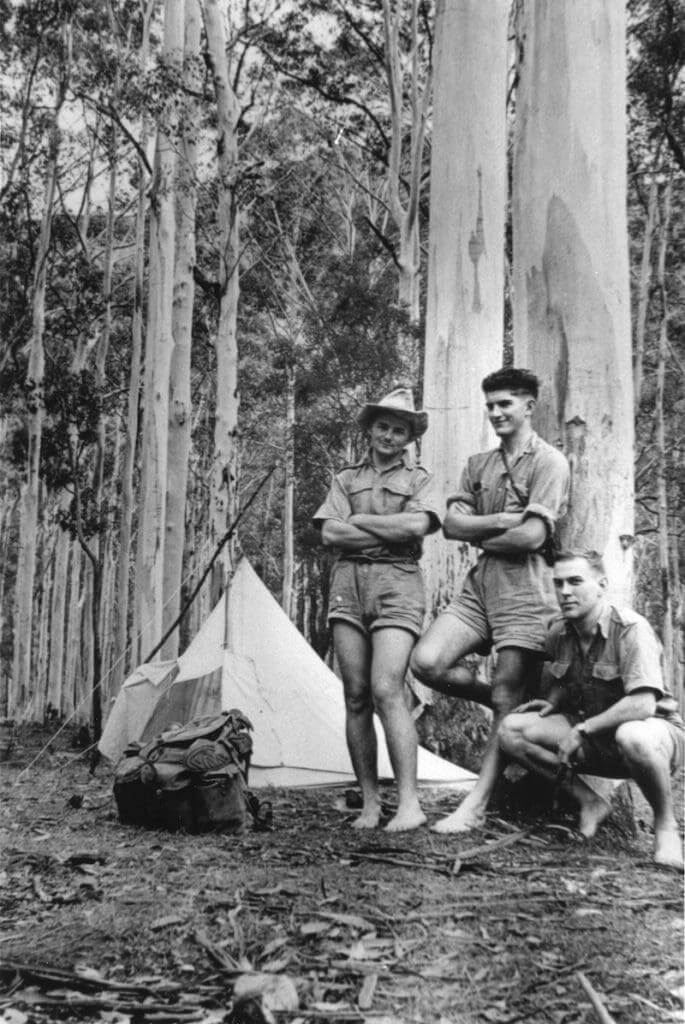

Such as Sydney Bush Walkers Club (1927), born from Myles Dunphy’s Mountain Trails Club (1914), as the first mixed sex walking club in Australia, which in turn led to the creation of the Coast and Mountain Walkers (1934) and The Bush Club in 1939.

With early interest in clubs focussed on Tasmania and the eastern States, soon clubs (and later, Federations) emerged elsewhere.

Key clubs in Tasmania’s early days were the Hobart Walking Club from 1929, with Launceston Walking Club forming in 1946. Meanwhile, across the Strait Melbourne’s Women’s Walking Club in 1922 was Australia’s first women’s only club and the Melbourne Bushwalking Club kicked off in 1940.

To the north in Queensland, it’s been suggested that the warmer, tropical climate led to the state lagging behind in terms of organised clubs. However in 1931, the Boomerang Walking Club (YWCA) was established as a women’s only club, with Brisbane Bush Walkers Club forming in 1948.

In Perth, locals created the Western Walking Club in 1937, with Perth Bushwalkers club established in 1969.

South Australia joined ranks in 1946 with Adelaide Bush Walkers club and in 1974, the Darwin Bushwalking Club was established.

Members of clubs tended to be young, educated, middle class professionals and in the words of legendary walker Dot Butler, ‘…was notable for having more eccentrics to the acre than any other body of people in Sydney.’

Whether it be gentle ambles, for health and discussion, like the white collar professionals of the highly regulated Wallaby Club, or the sporty race walkers of the MAWTC, one thing these clubs had in common in the early days was that they were for men only.

Not only were the trips considered too rigorous for ladies (whose countenance was better suited to the burgeoning ‘tourist walks’), but there was also an element of gentlemen’s clubs, providing men a chance to ‘be men’ together without the interruptions of ladies.

It’s no wonder then, that in 1922 the female wives and girlfriends of the MAWTC, rose up to create their own club, The Melbourne Women’s Walking Club, who are still active today.

With any organisation or movement, good leadership is key. And so it was within the clubs of the 1930s and 40s, whether by accident, ego or design, there arose key people throughout Australia to build upon the foundations of those who’d gone before. These were the pioneers of the club movement and for any keen student of bushwalking history today, their stories (of both adventures and campaigns) are epic.

Apart from Myles Dunphy, Dot Butler and Marie Byles in NSW, Jack Thwaites, Henry Judd, Ron Smith and Jessie Luckman in Tasmania, Richard Hemmy in Victoria, and Warren Bonython in South Australia, and there were many more.

It was during post WWI that another technological change started to affect the experience and exploits of walkers. The introduction of the motor car. Although it would appear a helpful tool in getting to walking areas, the post-war boom, saw their numbers double between 1918-1922.

Up until now, many walkers would choose to walk on access roads and tracks. The increase of cars, was just one reason that some walkers started pushing off-track, seeking a quieter connection with nature, with no sign of man.

And here we catch a glimpse of an attitude that emerged that can pervade our walking experiences to this day. The elitism and judgement from one type of bushwalker to another, which appears to have stemmed from another major development of the time – tourism.

“Increasingly, a ‘real’ walk would be defined as one through pathless wilds and the only desirable human contact would be with other bushwalkers,”

Melissa Harper

The Tourists

From the time Lady Franklin commissioned the building of shelter sheds on Mt Wellington, Tasmania in 1843 to support Hobart’s pleasure walker, to today’s creation of walking experiences like the Great Ocean Walk or Three Capes Track, State Governments and increasingly, commercial operators have recognised the benefits of such facilities.

Benefits, originally identified as purely for health and wellbeing reasons, with local farmers or miners stepping into the burgeoning need for local guides and accommodation, a new economy of nature tourism grew.

All around Australia, places of natural beauty were being opened up and experienced by people with no previous nature walking experience.

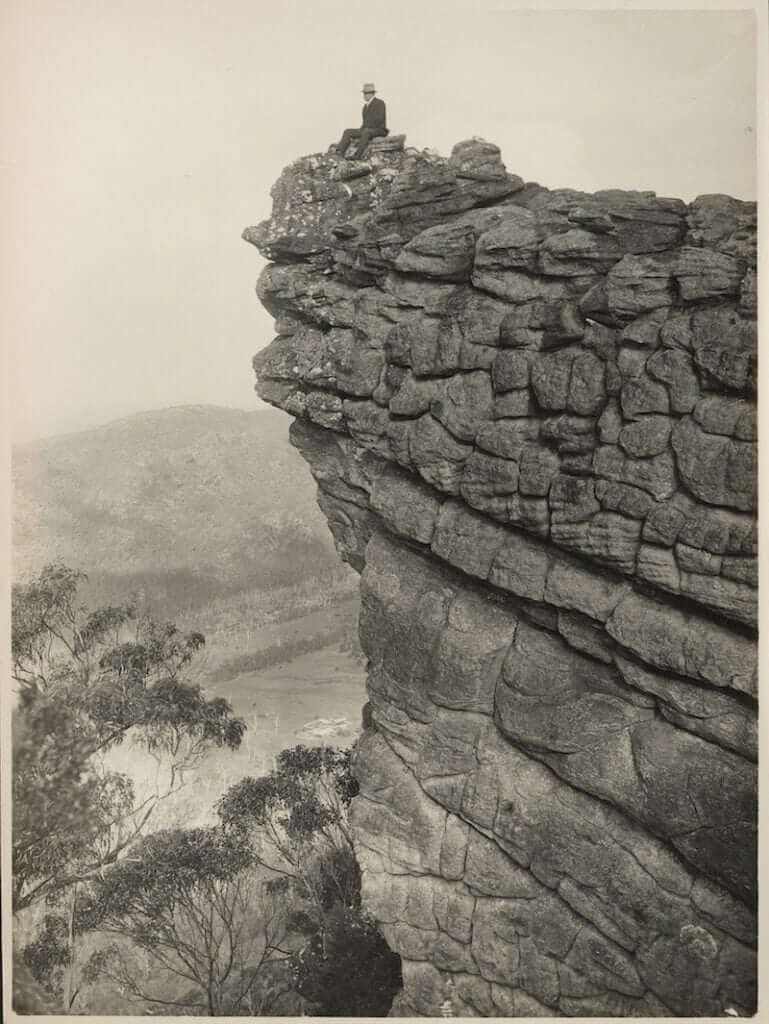

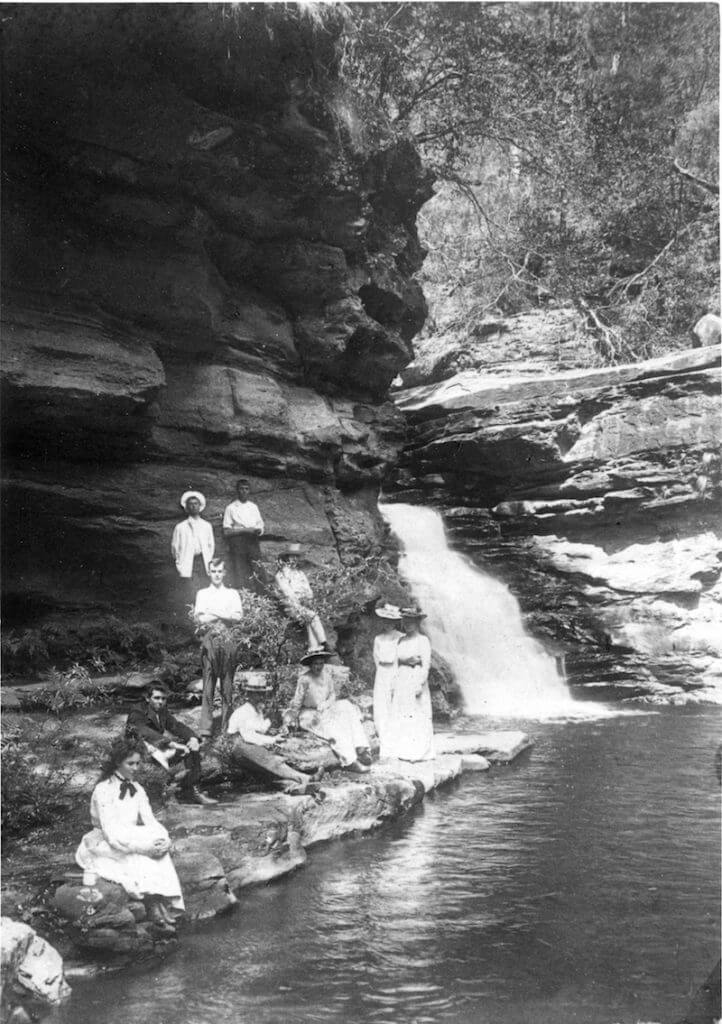

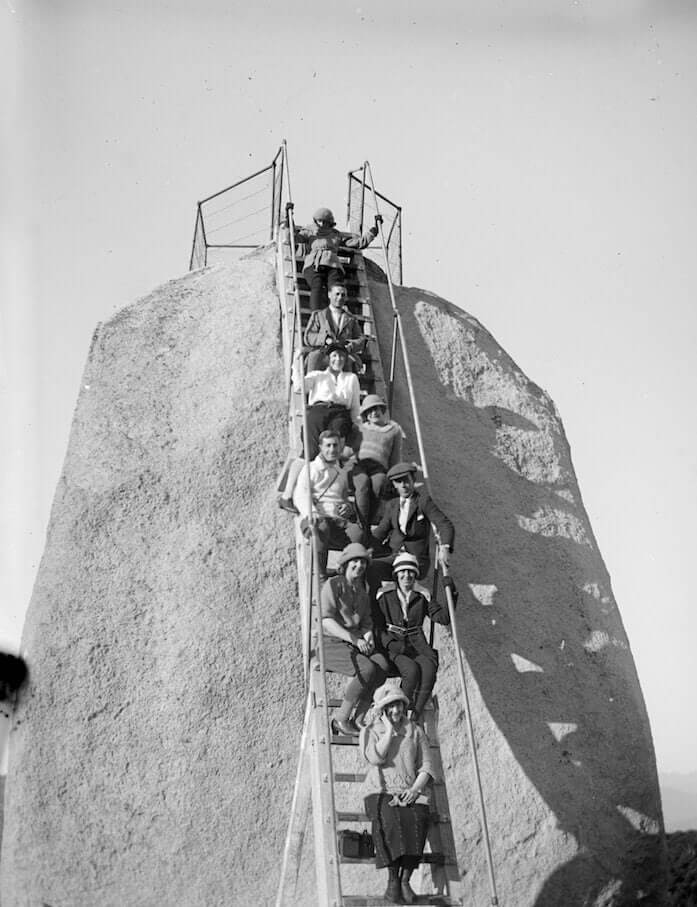

Leading the development was the Blue Mountains in NSW, which by 1900 was already the premiere tourism resort in Australia. A keen destination for honeymooners and others seeking to, ‘take the mountain air’, away from smoggy Sydney.

The Tipping Point

Although momentum and interest in walking had certainly been growing throughout Australia’s first century, it remained a fringe pursuit, embraced by a relatively small group.

It was Australia’s response to the devastating effects that World War One (1914-1918) had on the identity and health of our new nation, that propelled recreational walking into the hearts and minds of the general public, and saw it taken up with almost cult like compliancy.

With an evangelistic tone, the government and society encouraged all people to embrace physical activity as a way of strengthening our bodies and minds. Building our bodies, meant rebuilding the Nation.

Improved rail and transport links aided the marriage between enthusiasm and tourism, with guest houses and track networks welcoming this new happy couple.

No better was this enthusiasm evident, than in the ‘Mystery Hikes’ hosted by the Railways in 1932. For two shillings, thousands of city dwellers, would pack into train carriages for Sunday journeys to places unknown.

All around Australia (except in Adelaide where the city of churches initially rebelled against the concept of hiking on Sunday), new walkers were being introduced to the wonders of walking in nature, along with a festive atmosphere, supported by ambulances for blisters and refreshment vendors. All manner of attire was found on these outings, from the naive or straight laced lady retaining her heels and frock, to the daring ones who adopted mens shorts with long socks. One of the largest recorded events was 8,000 people, packed into 12 trains heading for Cowan Station, north of Sydney.

Demand was high for guidebooks and instructionals on walking in Australia, with both the Railways and experienced walkers penning works to satisfy every rambler. Works included Sydney Bush Walkers Club member Paddy Pallin’s, “Bushwalking and Camping”, published in 1933, just three years after he started making lightweight tents and rucksacks, specific to the Australian experience.

Early walking tourism developments

Blue Mountains, NSW

With the declaration of Public Reserves for areas like Wentworth Falls and Katoomba in 1888, guidelines were put in place for the protection of these places, with the emphasis not on environmental grounds, but for the enjoyment of people. It was within this Reserve system that track makers, like Irish Immigrant Peter Mulheran, worked tirelessly to create a network of walking tracks, with nods to his celtic heritage. Tracks, railings, stairs, bridges and celtic stone walls, were built along the cliff edges and to key pleasure grounds like waterfalls in the Valley of the Waters in Wentworth Falls and lookouts like Princes Rock.

Mount Buffalo, VIC

Mount Buffalo Chalet in the High Country near Bright, was opened in 1910 by the Victorian Government, providing employment to locals like Alice Manfield, daughter of a hotelier, as a walking guide. With control of the chalet handed to the Railways in 1924, thousands more visitors were able to make rail and coach connections from the cities, to take the mountain air. It has been closed since 2007.

Lamington National Park, QLD

In Queensland, O’Reilly’s Guesthouse saw the shift from farming to tourism for this tough mountain family in 1915, along with the newly declared Lamington National Park. Mick O’Reilly was made the first paid ranger in 1919 and O’Reilly’s Rainforest Retreat is still in operation today, a bird and nature lover’s retreat.

Cradle Mountain, Tasmania

It was passionate walkers, Gustav and Kate Weindorfer, inspired by the operation at Mount Buffalo, who set about opening the first hut at Cradle Mountain in 1912, called Waldheim.

In part two, we learn about why all was not sunny days and picnic singalongs…

A version of this article by Caro Ryan first appeared in Great Walks Magazine.