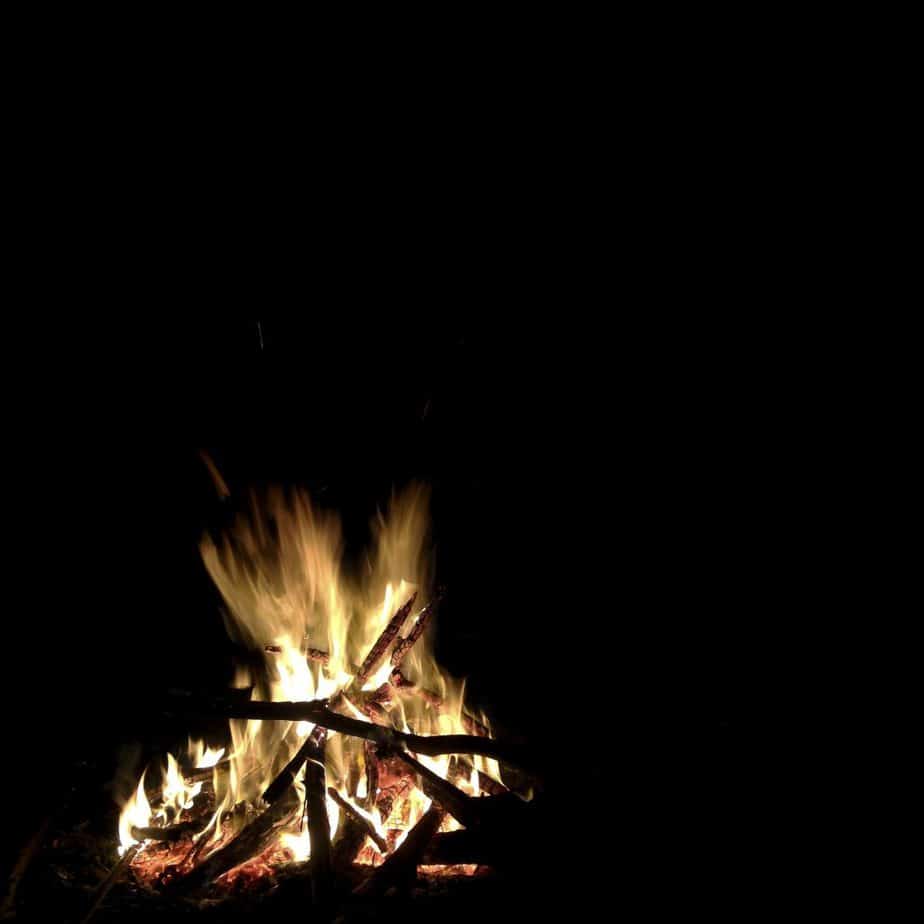

Often called ‘the bush television’, a campfire is one of those experiences that draws us to spend time in the outdoors and is the stuff of great memories. The warmth, the crackle, the nurture and build, the dancing of flames and the easy conversation that flows (like a good red) around it. As lovers of nature and wild places, where the practice of minimal impact bushwalking (MIB) or Leave No Trace (LNT) principles guide us to leave these precious places we visit, as good (or better) than we found them, knowing how to build a leave no trace campfire is an essential skill to master.

- Things to consider when choosing to build a campfire

- Why do I want a campfire?

- Is there a total fire ban? Are conditions dangerous for bushfires?

- Am I camping in a fuel stove only area?

- Is there enough wood?

- Is there an existing fire place?

- How to clean and rehab an existing fire place

- How to build a leave no trace campfire

Things to consider when choosing to build a campfire

As with anything in life, there are different opinions about what is best, right, proper or effective. Did I hear someone say ‘bushwalking’ versus ‘hiking’? Tent versus fly? Stove versus fire? There are people who on reading this are already riled about the thought of campfires in the bush, believing that fuel stoves are the better alternative to outdoor cooking. Then there are others who feel passionate about having no hot food or cooking in the bush at all, tracing the amount of energy and industry needed to make gas canisters, refine fuels and their transport as being just as bad in terms of greenhouse gases and trace-leaving footprints.

At the other end of the spectrum, are bonfire-building, tree-cutting, fairy-ring creating, ash and coal leaving folk who see it as part and parcel of any good night spent in the bush and wouldn’t think twice about pulling out the chainsaw.

There’s all different shades of grey within the two extremes, with nuance for each circumstance and location. For me, before making a decision to have (or not have) a campfire, I try to bring myself back to the foundations of Minimal Impact Bushwalking and ask myself what’s at the heart of the issue?

Although I prefer to use the Aussie term MIB (over the US ‘Leave no Trace’ campaign), the outcomes are the same and are based on roughly the same principles. Essentially, will there be any obvious evidence that I was in a certain location? Will it look the same for the next person who comes along, with the same desire as me, to find a quiet, remote, seemingly untouched part of the bush to camp in? Am I able to offer the gift of that experience to the next person, rather than imposing on them the history of my story?

Why do I want a campfire?

There’s lots of reasons why we might want (or need) a campfire. Cooking on a fire is a tradition in many bushwalking clubs and families and comes from a long heritage before the days of portable stoves… even before the Choofa! When it comes to needs, having a fire could be essential for treating or avoiding hypothermia, which can also be treated with warm food and drinks. For all the reasons of wanting a campfire, some are more wanty than needy.

- heat and warmth

- cooking

- boiling water to treat it

- entertainment/companionship

- signalling in emergency (make sure you fully extinguish a signal fire when a helicopter approaches… bushfires have started this way!)

- ancient rite by full moon 😉 (?! cue Outlander music)

Is there a total fire ban? Are conditions dangerous for bushfires?

It’s one of those things to check before heading out for a hike or bushwalk. Like checking you put petrol in the car and food in your pack along with everything else you need, checking the weather and fire conditions is key. Generally speaking, a total fire ban will mean not only no campfire, but no stoves as well, but check the fine print from your local fire authority. There’s also Park Fire Bans which have different rules, so make sure you check both.

To be honest, if there’s a TOBAN (or Park fire ban) in place, it probably means that conditions out in the bush will be pretty hot and heavy, so you might want to ask yourself if you’re going to enjoy it out there anyway… on days like this, I’m likely to stay home or choose a cool, coastal walk or canyon instead.

Am I camping in a fuel stove only area?

All of the bush is precious, but some spots are more fragile than others. In places such as alpine areas, above the treeline, and in many parts of Tasmania, land managers (such as National Parks) have declared areas fuel stove only. In places like this, it’s an offence to light a fire and you could be fined. Not only potentially damaging the environment, but damaging your wallet as well.

Is there enough wood?

There are some classic old bushwalking campsites, (if you know, you know) where in seasons of good bushwalking weather, the amount of ground and fallen timber is pretty thin-on-the-ground. Stepping back a bit to think about our impact on an area, us two-footed, pack-carrying creatures aren’t the only animals who like to find homes on the ground. It’s not just about us. Whilst it’s always a good idea to source timber for fires from dead and fallen branches – not chopping down or breaking off from living trees – larger logs and timber can be homes to all sorts of creatures… furry, feathered or scaly. So if there’s not much around, think about leaving it for those who might need it for a home, rather than just for one night.

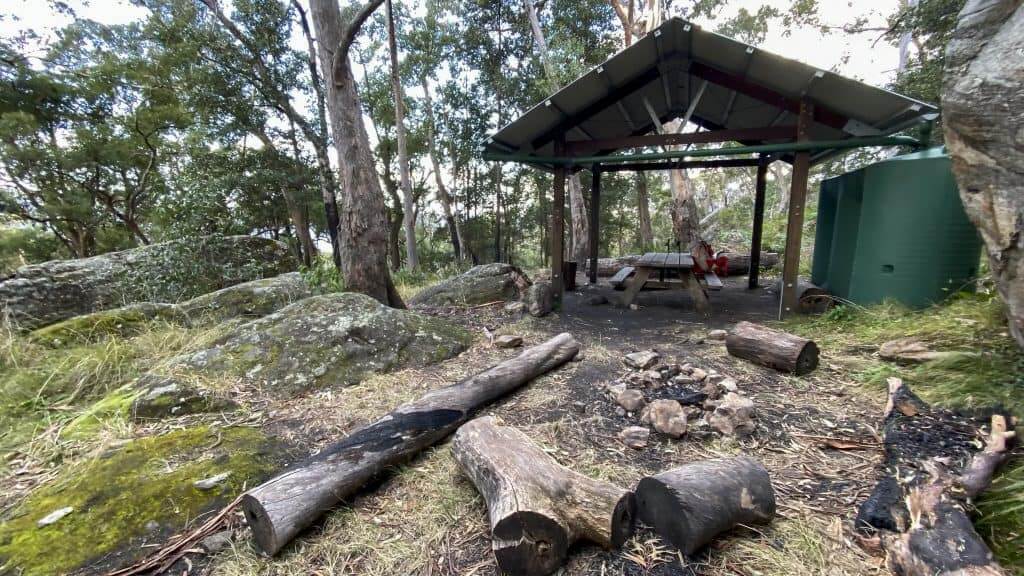

Is there an existing fire place?

There’s no need to reinvent the wheel… or add yet another fire site where one (or more!) already exist. If you do choose to have a fire, always try to use an existing fire site, especially when they’re provided by national parks.

It’s not uncommon to come across existing fire rings/places/scars that need some clearing out of old coals and even rubbish and stone removal. If we think back to our original concepts, the heart of minimal impact – to leave a place better for the next person – take a few minutes to rehab the area. It’s one of my favourite things to do on Clean Up Australia Day!

How to clean and rehab an existing fire place

- dig through the coals and ash and pull out all the rubbish (tin lids, fish tins, burnt rubbish, ring pulls and foil are common) to carry out with you.

- use your pooper scooper trowel to scoop out the coals and ashes and scatter broadly.

- reduce and remove any stones or rocks that have been built to create a ‘fairy ring’. These are unnecessary when making a fire. However, for inexperienced people, the ring of stones will signal to them that this is the place to build a fire. Exercise some judgement based on location, popularity and regular visitors.

How to build a leave no trace campfire

Choose a durable surface

Just like choosing somewhere to pitch your tent, it’s best to choose ground that is durable earth, void of plants, without the need for getting your Costa gardening skills out. Clear any leaf litter out of the way, far enough to ensure that it won’t ‘catch’, but keep it nearby as we will return it during the cleaning.

You need to be very careful around creeks and rivers, as river stones have a nasty habit of exploding when they get hot, sending sharp hot shards of rock flying. The bang is something else!

Don’t build a ring of stones

So, I can see why some people might think there’s a logic to having a ring of stones around your fire. Possibly to ‘keep it contained’ or provide wind breaks. But when you think about it, if you properly build, manage and supervise your fire, keeping it small, then a ring of stones shouldn’t be necessary. Shifting a stack of stones for a fire, is kinda like building rock cairns for sculptural purposes. If we go back to our minimal impact concepts, it is leaving evidence (charring rocks, possibly disturbing insect/animal homes) when there’s no need to. Sure, it’s what Hollywood and some old Scouts will tell you, but it is necessary? Yeah, nah.

Keep the fire small

I’ve seen someone (hi Alex) boil a billy for a lunch cuppa with only a few of twigs and 5 dry leaves. The less you build, the easier it is to manage and clean up afterwards. Speaking of twigs, you can buy stoves that are made for firing up with a handful of twigs. My Trail Designs metho stove comes with adaptors to – hey presto – convert it to a twig stove.

Put it out completely

Another benefit of keeping your fire small, is that it’s easy to put out. It’s important to use water to ensure it’s fully out before you clean it up. If you’re camping away from a water source, remember to gather enough water not only for dinner/drinking, but to douse the coals. Oh, and yep, if you really need to pee on it… the smell is something else.

Clear out all the rubbish

I like to think that we have evolved past the bash-burn-bury days of our bushwalking and exploring forebears, however we’ve all come across rubbish in the bush and this includes in old fire sites. Once the coals are cold, I scrape through them with a stick and pull out anything man-made. This isn’t an article about what to burn or not to burn, but I will say that I will usually burn off my tins (like the one below) to remove the oil and smell, before adding it to my rubbish bag to carry out. Digging out the lid and ring-pull is part of it. If there are other people with me, I’ll poke through the coals to check there’s nothing else left behind, before moving on to the scatter!

Scatter the coals and ash

Grab your trusty poo-trowel and remove all the coals and ashes from the fire site by scattering (I fling!) them outside the area. Try and spread the love around a broad area, just watch out for the wind direction – It’ll chase you like campfire smoke.

Replace the leaf litter

This is my favourite part of creating a minimal impact campfire. It’s where we replace the leaf little that we’ve put to one side at the start and work at ghosting the site… like we were never there. If you want to get really good at it, take a before photo and see how close you can get to that.

Scatter gathered timber

There’s one last step to building a leave no trace campfire and that is scattering any excess timber that you may have collected, destroying your nice wood piles. I know it feels like a waste, but let’s come back to those principles; leaving a wood pile is leaving evidence that someone has been there. That’s what we need to avoid, so fling your timber with your best javelin arm and ghost your wood pile as well.