Is that really my alarm going off at 3.15am? I confess that I’ve always had an aversion to commercial guides who insist on waking you up for an early start, but in this case, I’m happy to let my circadian rhythms crash out of any sense of timing and drag myself towards breakfast at stupid o’clock.

There’s quiet nods all round in the foyer of O’Reilly’s, (the legendary guesthouse and touchstone for generations of bushwalkers) as our quiet band of 13 walkers + 2 guides, adjust packs, head-torches and command our intestines to digest the aforementioned early morning fuel.

I haven’t seen this quiet nervousness since the last funeral I attended, when vaguely familiar faces averted their eyes and studied their feet, before making small talk about weather and restless sleep.

Then, like the crack of gates swinging back at the start of the Melbourne Cup, we were off.

But just like the horses at the start of a long race, we were forced to leap away and bound forward, at a pace that surprised even the most experienced. It wasn’t as though we hadn’t been warned. Over the past 6 weeks, we’d had regular phone calls and emails ensuring we knew what we were getting into and our briefing the night before cemented our steely resolve. Our guides were using the relative luxury of the well-formed Border Track and then the Albert River Track to leap ahead, in darkness, before we were forcibly slowed by the tenacious force of the living, breathing Lamington National Park‘s sub-tropical rainforest and it’s deep tendrils of lawyer vine and fallen timber.

The leaping though, was all planned and well calculated. Not only would it stand us in good stead to reach the end at Christmas Creek in 12 hours, well within summer daylight, but it was also designed to ensure that anyone who was struggling this early, was turned back on well-formed track before the point of no return. As it would turn out, our numbers were reduced with this strategy in the rush to sunrise and our wee caravan of courage was reduced to 12 for the rest of the 36 km undulating route.

Those of us left were mostly locals (or somewhat local) from the Gold Coast, the surrounding Hinterland or Brisbane, with myself the only ring-in from interstate. In these parts, O’Reilly’s is the stuff of childhood memories. It’s about first encounters with nature, traditional style family holidays and the winding mountain road to nowhere except this hidden hilltop heaven in the clouds.

With 90 years of history behind it, the accommodation at the Retreat is showing a few signs of age and wealth of story. Although there are plans for refurbishment (as well as taking over the management of the campground) if luxury is what you seek, then choosing to stay in one of their Villas (only 10 years old) is sure to hit your luxe spot.

The relatively rare guided Stinson Wreck walks that they run, are usually frequented by repeat offenders, and familiar friendly faces to these parts. They know the staff and they certainly know the O’Reilly family and its stories. In true O’Reilly way though, I was made to feel like one of the family, for this is what O’Reilly’s is about… family. Currently run by the 3rd generation, it’s destined to always remain in family ownership. The challenge will be to see how they can adapt and develop the brand and their product offering as times ‘down the mountain’ change below and around them.

But what with the increased interest in adventure and physical challenges over the last few years (think Oxfam TrailWalker, Everest Base Camp, Kokoda, etc) and folks like me sharing stories online, I wonder if one of the keys to their future is actually about looking back to the pioneering spirit of Bernard O’Reilly and the story of the Stinson.

If you’re not familiar with the tale, it’s a oldie, but a goodie.

It’s one of those stories that should be told and re-told in high schools across Australia. It not only tells of mateship, backing yourself and strong community ties, but deep courage, heroism and an undeniable faith.

In a nutshell, it was 1937 when a mail plane flying between Brisbane and Sydney disappeared one night amidst cyclonic weather conditions. Whilst the rest of the world believed it to be downed somewhere in the Hawkesbury River, north of Sydney, Bernard O’Reilly, a toughened (yet gentle spirited) mountain man, put pieces of info together and wondered if it hadn’t come down near his home in the rugged and unexplored dense rainforest crests of the Lamington NP. Big picture wise, we’re talking 60 kms west of Coolangatta in what we know now as the Gold Coast Hinterland.

Working from his vast experience of the area, Bernard headed out from the farmhouse bound for Mt Throakban (1156m), where he would climb a tree and spy a distant, single burnt tree, on a far ridgeline. Pushing up and down gully and peak, he reached the burnt tree and discovered two men still alive after 11 days. [You can read the full story in Bernard’s book, “Green Mountains”. nb: The giveaway has now closed.]

And so we pressed on from a cloud fall sunrise at Echo Point Lookout that could’ve held my attention until sunset. Mist tumbled from ridges to the west, over peaks that we were soon to meet, with names like Ratatat and Mt Durigan, whilst the emerging sun drew itself up from the Nerang River to the east. Too soon we were pulled away and urged ever onwards by our guide Mark, making the most of the ‘good’ track before slowing to approx 2km/hr on the undulating yo-yo’s of this classic ridge walk.

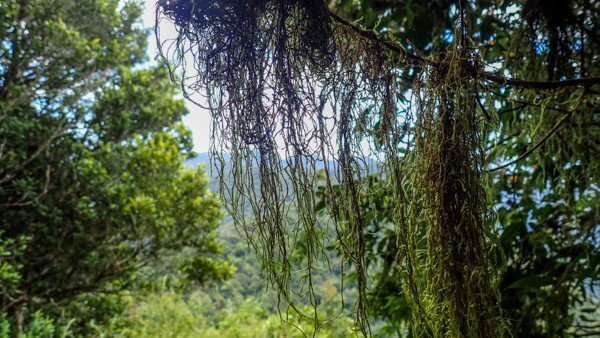

The rainforest heaved around us as the ground constantly rose and fell along the Border Ranges. Clues to the fiery, volcanic past of the area were spotted in the moss covered geology and occasional glimpses from the canopy, which hung over us turning day to dusk.

Onwards, onwards, upwards, downwards. The pace only slowing slightly to scramble over chest high fallen timber or to release the Velcro grasp of bush lawyer from our heads and bodies.

Watch the video above to experience what the 37km trek is really like!

What makes this walk tough, isn’t any of the singular aspects of the day. It is the combining of it all in a giant snow-ball of determination. The early start in the dark, the heat and dripping humidity, the hide and seek of the route, the steeplechase of rough terrain and the relentless pace required to complete all 37 kms in 12hrs.

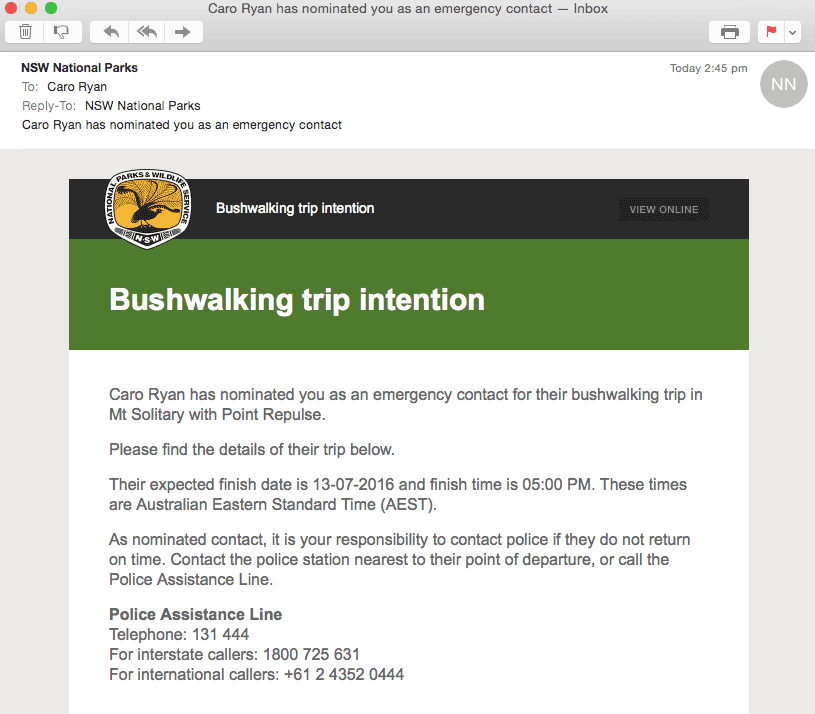

Of course it’s possible to do this walk over two days (camping permit needed) and there are local bushwalking clubs (Gold Coast Bushwalkers, Southern Queensland Bushwalkers, Brisbane Bushwalkers Club) and experienced independent walkers who do this. There are minimal tent sites that can be squeezed in down below Ratatat and at Echo Point Lookout, with a larger area at Point Lookout or at the clearing above the crash site.

But this guided walk from O’Reilly’s has a touch of the “let’s feel what they felt”, about the day – the way that some war or historical walks often do. We did it tough, because Bernard and the survivors of the Stinson did it tough, but we were under no illusions that our temporary ailments were anything compared to the physical, mental and emotional challenges that they went through.

Arriving at Point Lookout at 12 noon, we demolished lunch long enough to pull off a few of the leeches that had come along for the ride. There was certainly no time to stop and remove them along the way. Little did we know, that we had made perfect timing, with the other group of walkers, who had approached from Christmas Creek using the 7km ‘Rescue Route’, joining us only 10 mins later. After taking in one last epic view across into NSW we turned north to head down the ridge towards the crash site.

With our journey taking place on the 80th anniversary of the crash, it’s no surprise that there were quite a few people keen to experience the silence and verdant grave. As I moved forward and down, grabbing onto yet more tree roots, along with anything else I could find, I was transported in my mind to imagining the sounds of that fateful night.

The sounds that surrounded these six men, inside the tender Stinson, as it was buffeted by cyclonic winds – creaking, yawning, howling. The nervous tension as the pilots (Captain Rex Boyden and Flight Officer Beverley Shepherd) tried in vain to control the force of nature and the image of hands grasping airline seats through prayers, whilst sweat poured from foreheads.

What must the sound have been like? Of tearing metal and screaming engines ploughing into nature, defiant against the defence of man, at the whim of the wind. Was there a deafening silence after the invader pushed itself into the ground before fire took hold, as if to prove that nature was indeed in charge? For here, nature will always be in charge.

To call this jungle dense and impenetrable, is a lazy tabloid description. And so it is to an invisible band of local volunteers who respectfully maintain the tracks to the site of the crash and also to that of Westray’s grave. That lonely spot lies beside one of the most peaceful, singing creeks and under the most gentle pastel light that I have ever seen.

For me, the journey to the crash site was the closing of one circle and the reminder of one that is still undone. To have had my own bushwalking history informed by the writings of Bernard O’Reilly from his time living in the Kanimbla and Megalong Valleys in the Blue Mountains, with boyhood adventures of the Coxs River and mountains that I now call home (including Mt O’Reilly), and to then be able to follow him and his gentle, creative spirit to these green mountains of his was the realisation of a dream. But it was also the reminder of the little Cessna VH-MDX that remains unfounded, deep in the Barrington Tops of NSW, with five men aboard, after it too succumbed to nature in 1981. These men lie silent there, waiting for others to connect the dots to their story and close their circle.

After taking our own time to spend a few hushed moments at the crash site, the group gathered at the clearing above as 3rd generation O’Reilly, Jane, read from Green Mountains. As she read the words Bernard used to describe coming across the crash site and two men alive, after 11 days, her voice broke and tears welled. The true depth of the significance of their story was shown in her own.

Afterwards, the combined groups split once again between those who felt physically fit and fast to descend quickly to the trailhead at the ford (450m descent in 7kms) and those who needed to amble back, nursing injuries, knees or fatigue from the day. We were spurred on knowing that cold drinks and snacks were waiting for us at the bottom.

I’ve heard that some people have been critical of certain aspects in which the O’Reilly family business has worked to share the story of the Stinson, perhaps viewing it as exploiting disaster for commercial gain. But to stand in the cellophane green light of that clearing and to hear Jane reading from one of the oldest editions of the book after having walked the 37 kms with her, there’s no doubt in my mind her sincere and authentic desire to keep the story known for all the right reasons.

If you’ve got a love for Australian pioneering bush spirit, stories of true heroism and importantly the right fitness and bushwalking experience, I can’t help but think that you’d love the experience and I thoroughly recommend it.

Perhaps as the years roll on they will need to temper and adjust the way they tell their family story. As years of O’Reilly’s Saturday night bush dances fade further into memories and as all organisations must adjust to remain relevant, the challenge is how they stay true to their heritage, whilst reaching new generations. New generations who crave meaning and authenticity, adventure and heroes, whilst balancing an acutely sharpened sense of cynicism and mistrust of traditional marketing.

Caro travelled courtesy of O’Reilly’s Rainforest Retreat and Gold Coast Tourism.