Part 1 – How to Read a Topographic Map

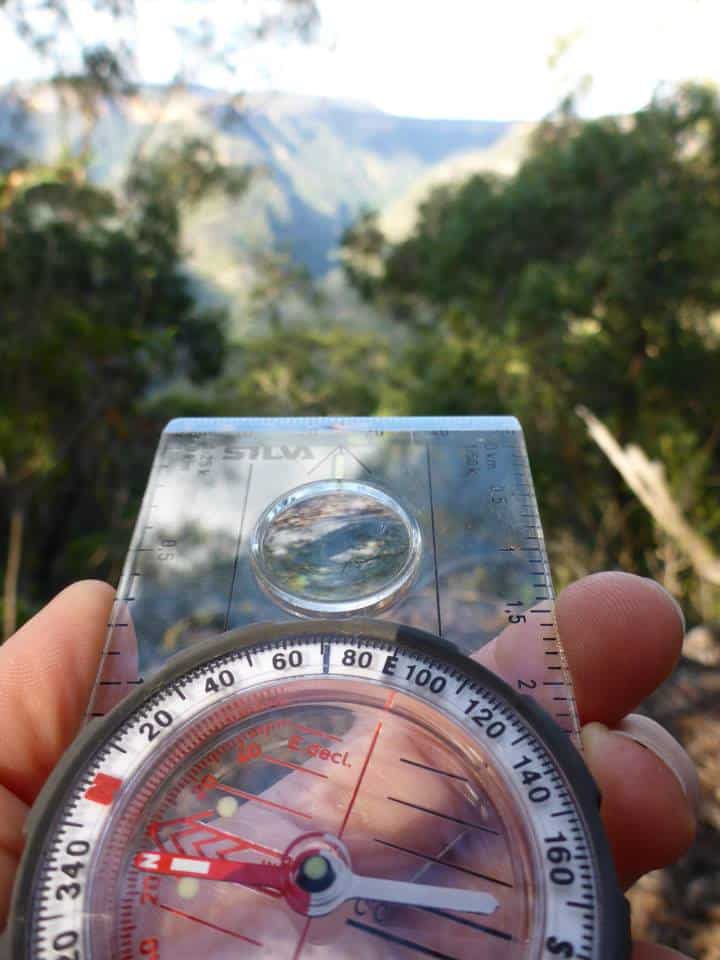

One of the major excuses I hear from people (mostly women) not wanting to step up and lead hikes or outdoor adventure trips is their lack of navigation skills. I feel that like so many other things in life, although some people may demonstrate a natural ability with directions (like an inbuilt GPS), it is possible to learn how to navigate, with practice and patience being one of the keys.

To help remove some of those barriers to adventure, I’ve decided to create a series of posts to help with some of the basics of navigation, starting with map reading and moving onto to using a compass.

Why should I learn how to navigate?

Over recent years, with the development of GPS technology and the rise of ‘the device’, more and more people have been relying on their smartphones, watches or simply a handheld GPS, to inform their walking experience.

Although these gadgets can be extremely helpful, (I use them myself), there is a danger that we all become too reliant on these pieces of technology, without understanding their limitations and potential for failure. There’s a lot more that can go wrong with a iPhone than with a map and compass. In addition to these navigation aids, there’s the important skill that comes from understanding and reading landforms (as well as sun, moon and stars) and the environment around us, separate to any man-made aid.

Gaining Confidence and Understanding

There’s real comfort that comes from understanding our world around us in a bush setting. It gives us the ability to plan routes and adventures, picking the easiest (or most scenic) way of getting from A to B and from a personal security point of view, could be the difference between finding your way home, or not.

It’s one of the key reasons that I’m a strong believer that anyone who spends time in the bush should have a basic level of map and compass skills. I feel that it can not only be of practical assistance, but can massively enhance your experience out there as you begin to see things differently.

In this series, I’ll be covering off the basics of navigation, beginning with map reading and a few other foundations, before moving into the art of navigating with a compass.

A really good starting place, is to think of navigation as a mystery story. You are playing the role of the detective in a tale of intrigue and cunning. All around you are clues, both subtle and not, that if you know what you’re looking for, will help you solve the mystery. Before you know it, it will be like you’ve flicked to the last page in the novel, slammed your finger down on the map and announced, ‘Aha! I know I am at point A and I know the best way of getting to point B AND how long it will take.’

What maps should I use for hiking?

The best maps for hiking are topographic (aka “Toppo”) maps, meaning that they include visual representation of the topography or natural landforms for a particular area.

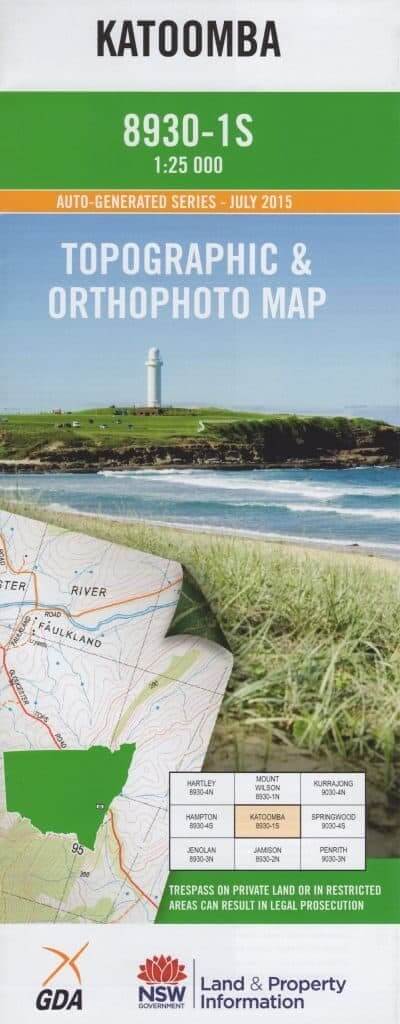

Toppo’s come in a variety of scales, with the most common ones for bushwalking being 1:25,000, where 1km is equal to 4cm or 1:50,000, where 1km translates to 2cm. My first choice would always be 1:25,000, if available, as it gives lots of good detail, especially for the more subtle features.

You can buy printed toppo’s from specialty maps stores, government Lands Department offices in each state or outdoor gear shops. Just note that most gear shops will only stock the most popular maps or just those for their region, so don’t rely on picking up a map from a local store on route to a trip. Not only may they not have the map you want, but by getting your hands on a map well in advance you can plan out your route, get a good idea of it ‘in your head’ and think through problems or challenges that you may encounter.

Topographic Map Names

It’s important to note that all toppo maps have a name. Although it will usually be shortened to something like, “Katoomba 1:25K, 3rd edition,” in some circumstances, such as an emergency, it may be important to be able to refer to the map with it’s full name, eg: Katoomba 1:25,000 8930-1S, 3rd edition.

OK, so now you’ve got your map (I’ll be referring to the Katoomba 1:25,000 for this post), what are the basics you need to know or the clues to solving the navigation mystery that you should be looking for?

Gridlines

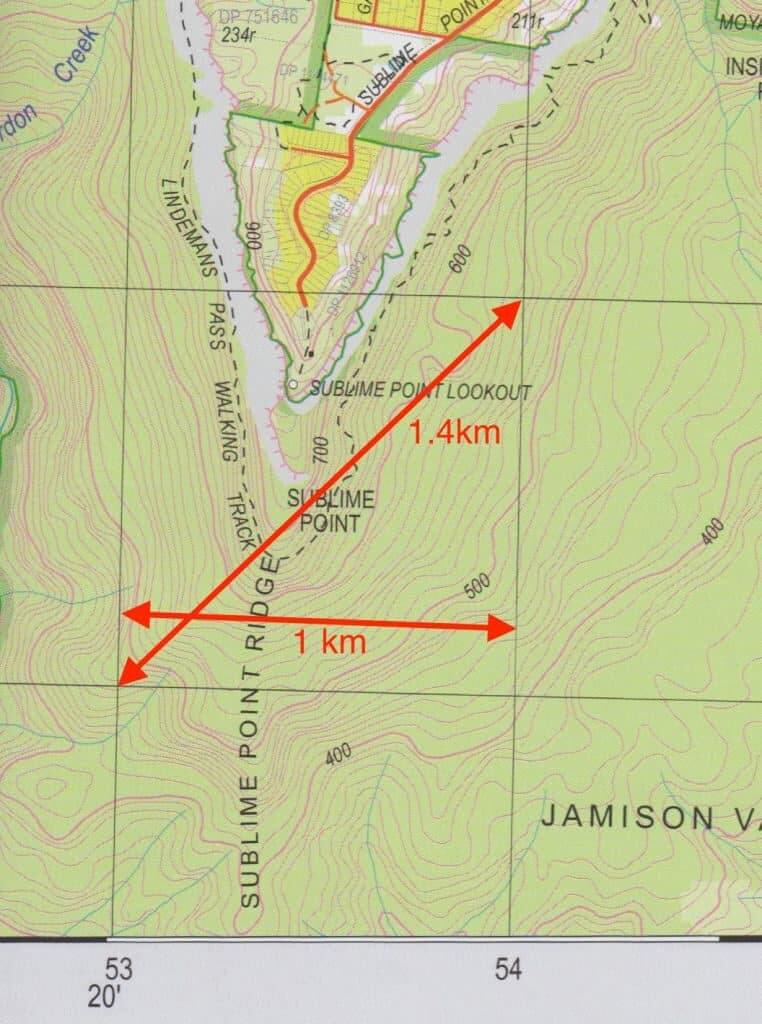

Looking at the map below, you’ll see that it is divided up into 4cm squares or grids.

These are called Gridlines collectively, or Eastings for the vertical lines and Northings for the horizontal ones. On a 1:25,000 map, the distance from one side of a grid to the other (parallel) = 1km. Diagonally across a grid is 1.4kms.

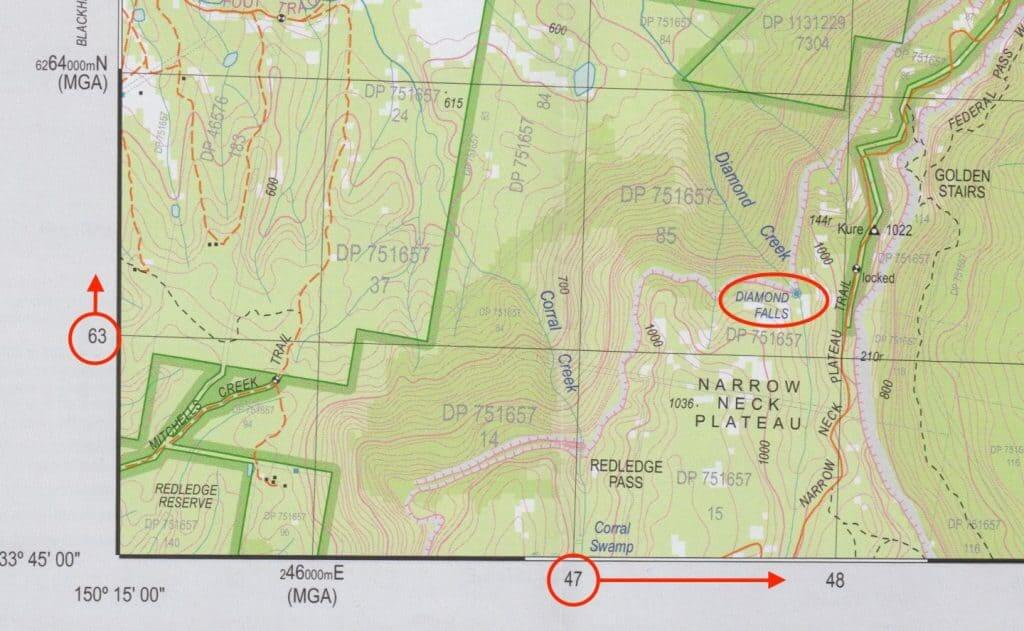

There is a numbering system for these grid lines to allow you to identify a particular spot on a particular map.

This system of numbers on Aussie maps is called Map Grid of Australia (MGA) and is based upon the UTM (Universal Transverse Mercator). It is very similar to the MGRS (Military Grid Reference System).

The series of numbers is known as a Grid Reference.

Grid References

In bushwalking terms, a 6 digit reference (within 100m accuracy) is usually sufficient unless you’re needing to be very specific, in which case an 8 digit reference (within 10m accuracy) gives more detail. You could think of this like adding a decimal place, rather than rounding to the nearest whole number.

Each gridline has a 2 digit number that is printed on the margin of the map. The space between that line and the next is broken up into 10 invisible lines, each representing 100m distance.

Therefore, the grid reference for Diamond Falls on the example below is: GR 477 633.

What about Latitude and Longitude?

“Lat/Longs” is a different system of defining your location and generally not used by recreational bushwalkers or hikers. This system is more commonly found in 4WD-ing or tattooed onto Angelina Jolie’s arm. It is also used by emergency services and the military as something of a universal language in describing location. The good news is that increasingly, emergency services and 000 operators are able to accept and translate UTM/MGRS grid references to Lat/Longs for purposes such as helicopter rescues in remote locations, so don’t stress that you need to learn a second system on top of the existing one. [NB: Toppo maps include all the information needed to use the Lat/Long system and you can find out how to do so in a short video over on my YouTube channel!

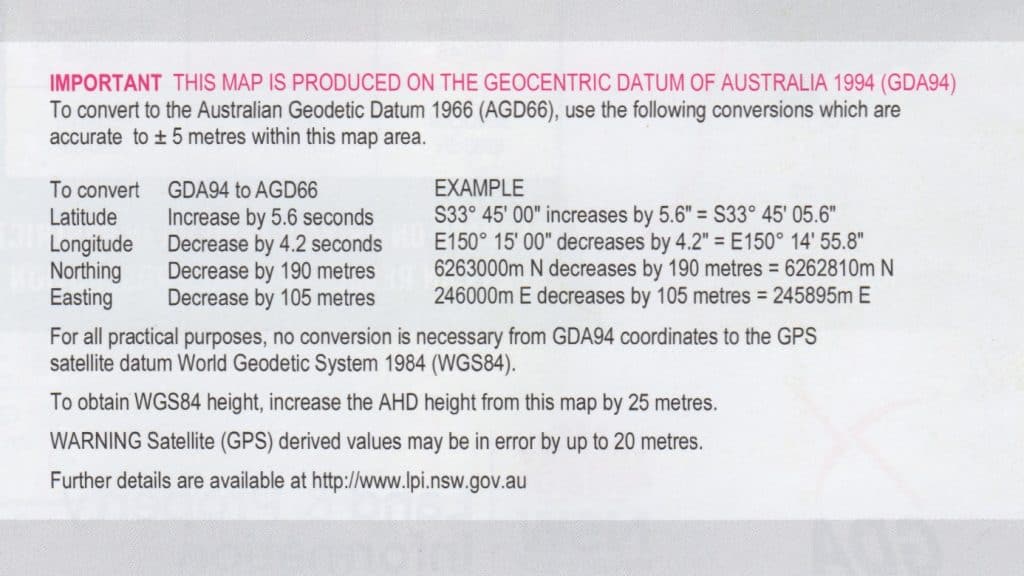

Map Datum

As government mapping agencies (or as I like to think… The GMG’s – Great Mapping gods) create new printed maps for us worshippers at the church of adventure, they take the opportunity to use the latest systems (or dark arts) to develop each one. What this can mean to us in practical terms, is that if you have someone using a 2nd edition of the same map (whilst you’re on 3rd), that the Grid Reference for a specific point may be different to each other.

This is why it’s important to ensure that when you’re communicating grid references you ensure that you give the correct map name (and edition) and datum used with it. You can find this information in the maps key or legend.

Although this post is about navigation with a map and compass, another place where it’s important to take note of the datum of a map, is when using a GPS device or software. You need to check the settings to make sure that the correct datum is set for the map that you’re using with it.

This post is just the tip of the iceberg! If you want to learn more, I’ve published an 87 page book, How to Navigate – The art of traditional map and compass navigation in an Australian context. It goes into much more detail and is loaded with images, diagrams, how-tos, tips and tricks.

In Part 2 of this series, we’ll continue with the basics of map reading, looking at the different landforms and how to identify them on the map, as well as on the ground.

If you would like to do a navigation course and be guided through the steps, learning tips and tricks along the way, along with loads of practice, I’m running navigation courses for beginners with Blue Mountains Climbing School. Check out this post for details.

There’s also a whole range of events or organisations that can help you practice your nav: The land search and rescue squad that I’m involved with, NSW SES Bush Search and Rescue, run the annual NavShield event (2-3 hrs from Sydney) or get in touch with orienteering clubs, bushwalking clubs, adventure race organisers or rogaining associations.

This article first appeared in Travel Play Live magazine.