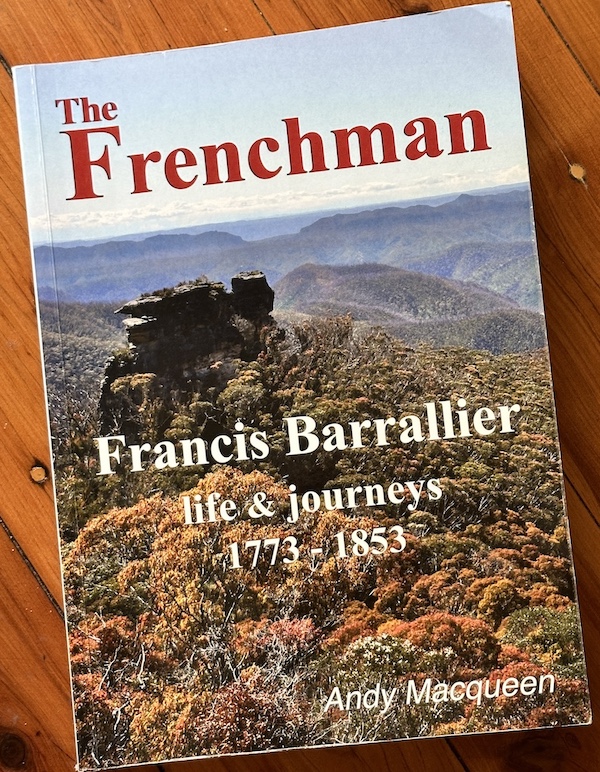

For those of us who find ourselves drawn to the rugged beauty and whispering histories of the Australian bush, Andy Macqueen’s “The Frenchman – Francis Barrallier Life & Journeys 1773-1853” is an absolute treasure. Macqueen, a name synonymous with bushwalking in New South Wales, particularly as a former president of Bushwalking NSW and 2024 recipient of the prestigious Chardon Award, brings his deep knowledge of the landscape and a historian’s eye to the fascinating story of Francis Barrallier’s early explorations. This isn’t just another dry historical account; Macqueen breathes life into a largely unsung figure, offering readers a captivating journey through colonial politics, early interactions with Aboriginal people, and the tenacious, often fraught, attempts to penetrate the formidable Blue Mountains.

Katoomba to Mittagong (The Ensign Barrallier Walk)

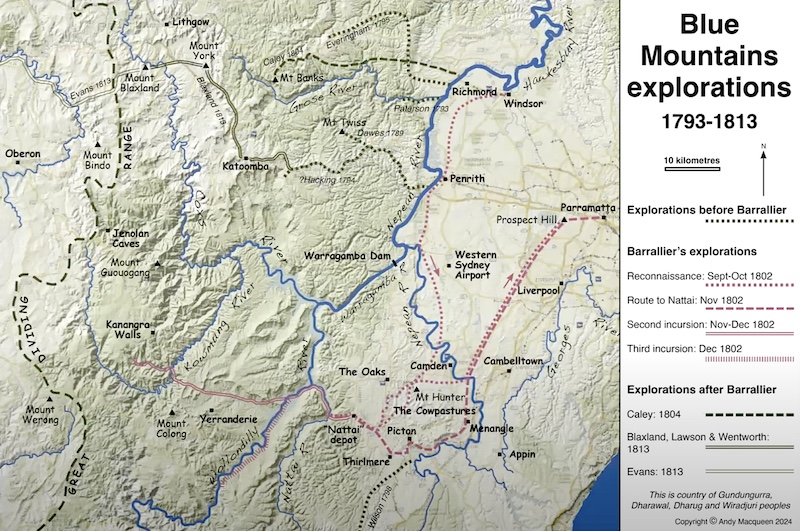

I first heard Barrallier’s name from Val Lhuede, on the verandah of the Yerranderie Post Office, during my first foray into multi-day bushwalking in 2001. I was on what I thought was the 132 km “Katoomba to Mittagong Walk”, but she set me straight—it is officially known as the Ensign Barrallier Walk.

Full of youthful naivety (and a whole cauliflower in my 23 kg pack), I set off with grand ambitions from Katoomba but only managed to reach Yerranderie before having to retreat. I’m forever grateful for the Catholic Bushwalking Club’s public shack on Scotts Main Range where I slept 14 hrs straight, realising I was out of my depth. It wasn’t until 2005 that I returned with NPA to complete the full traverse from south to north. Reading Macqueen’s account of Barrallier’s earlier struggles in that region adds a profound layer of connection to my own experiences.

“I see with satisfaction that the difficulties I have undergone and which at present appear insurmountable in passing these Mountains does not include you to abandon the project. To this moment, all my efforts have been ineffectual. Altho’ no pains or perseverance has been neglected in endeavouring to get to the westward nor have we been stopped by the steep Mountains and precipices we were obliged to pass to accomplish the mission You have charged me with.”

Translated letter from Barrallier to Governor King, 1805 (The Frenchman, page 78)

What was a Frenchman doing in the Blue Mountains?

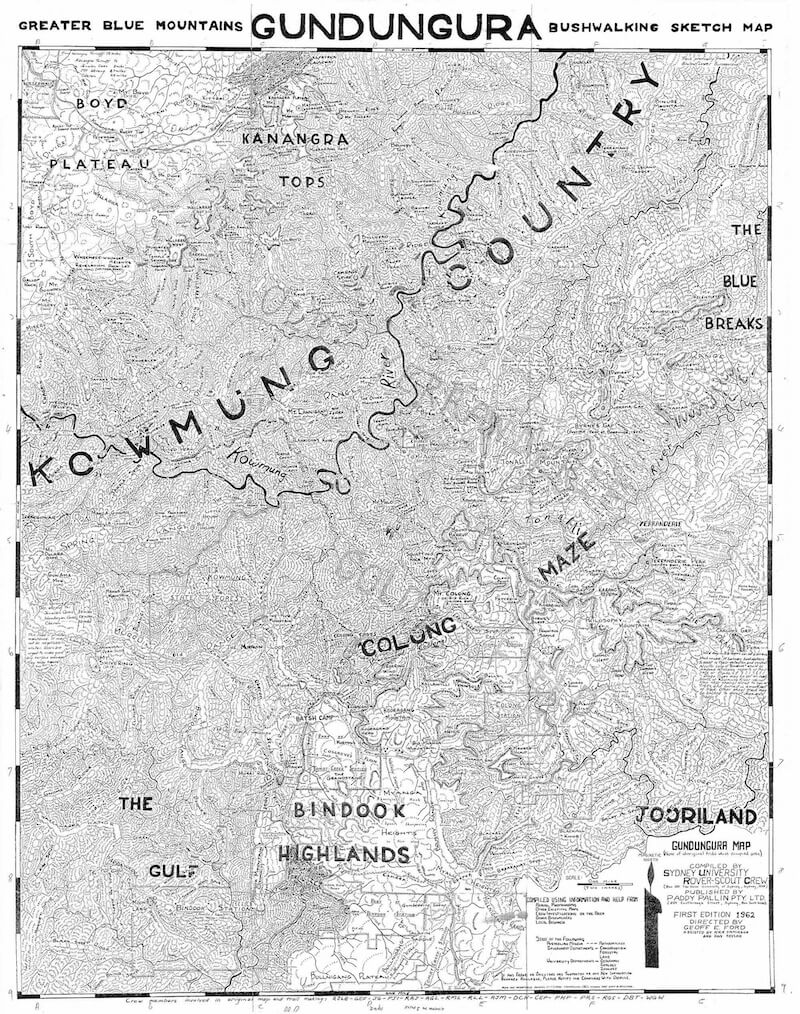

Inspired by the 1962 Sydney Uni Rover Gundungura map during some of his Kanangra adventures, MacQueen saw names like Barrallier Pass, Wheengee Whungee and Le Tonsure and he found himself wondering just that.

No stranger to these places he writes about, he’s spent countless hours traversing the very terrain Barrallier endeavoured to conquer, so his perspective is uniquely informed. He’s not just an “armchair Explorer” as he notes, preferring to get out there and follow “people’s tracks and people from the past” to gain a “better appreciation of what they might have been thinking”. This personal connection to the land and its history shines through every page and had me reading along with a topo map on hand.

But this isn’t the first time he has written about this fascinating immigrant, somewhat of a refugee from Napoleon’s regime.

“It took Covid 19 to bring my focus back. During a lockdown I pondered revelations published by Harry Steward, formerly of Clark University, Massachusetts. I thought about the other aspects of Barrallier’s life that I had stumbled on thanks to the wonders of the information age. And I thought how some matters in my 1993 book needed to be corrected. Above all, I realised that it would be worthwhile to re-tell the story of the expedition with more emphasis on the Aboriginal people whose country Barrallier invaded. An exercise in truth-telling.”

Andy MacQueen, 2024

A new translation – a new interpretation

Macqueen’s dedication to accuracy is further highlighted by his collaboration with linguist Milena Bellini-Sheppard on a new transcription and translation of Barrallier’s journal. This meticulous effort offers fresh insights into Barrallier’s experiences and observations, including his surprisingly detailed notes on the natural history he encountered, such as the first European recordings of brushtail rock-wallabies and lyrebirds, as well as observations of koalas and wombats.

This translation brought to light additional nuance and insights that demonstrate MacQueen’s original aim of having his second book on Barrallier contribute to the truth-telling dialogue.

Colonial politics

One of the central themes Macqueen expertly unravels is the intriguing political backdrop against which Barrallier’s expeditions unfolded. While the official line from Governor King (Barrallier was his aide-de-camp) was that he was embarking on “an embassy to the King of the Mountains” (ie. Goondel), Macqueen, drawing on King’s letters to Banks, makes it abundantly clear that the primary goal was far more strategic: to “find a way across the mountains”. This seemingly diplomatic mission was, in fact, a clever “ruse”. This glimpse into the machinations of early colonial governance adds a rich layer of intrigue to Barrallier’s journey, along with a healthy rivalry with George Caley—another intriguing character!

Aboriginal and European relationships

Beyond the colonial ambitions, the book provides a crucial perspective on the early encounters and relationships between the European explorers and the Aboriginal custodians of the land. Barrallier’s expedition relied heavily on the knowledge and guidance of Aboriginals like Dharawal man, Gogy. Macqueen highlights that some of Barrallier’s routes, such as the descent down Sheehy Creek, were “traditional Aboriginal routes”. What’s particularly noteworthy is Barrallier’s apparent understanding, documented in his journal, that “different Aboriginal people have different country” and that entering these territories required adhering to certain “protocol”. As Macqueen points out, this was a relatively advanced sentiment for the time, suggesting Barrallier possessed a degree of cultural sensitivity that was not always prevalent among his contemporaries. Katoomba local, Uncle David King, a Gundungurra Elder, even treasures Barrallier’s journal for what it reveals about his people.

However, Macqueen doesn’t shy away from the complexities. He notes that even though Gogy was familiar with the general region, he was “not necessarily welcome” in the country of the Gundungurra language group. This nuance underscores the fact that pre-colonial Aboriginal society was not monolithic; distinct “boundaries and potentially complex relationships” existed between different groups. This understanding adds a vital layer of depth to our appreciation of the historical context.

Earlier than Blaxland, Wentworth, Lawson

For bushwalking enthusiasts, “The Frenchman” offers a fascinating look at the early attempts to navigate the formidable Blue Mountains, long before Blaxland, Wentworth, and Lawson claimed their populist crossing. Macqueen meticulously details Barrallier’s various “incursions” – a term the new translation of Barrallier’s journal uses, carrying a different connotation than the gentler “excursions” – taking us down Sheehys Creek (approx 20km SE of Burragorang Lookout) to the Nattai River (an area which Barrallier likened to the “Scottish Highlands”), and along the Wollondilly River. Most of the areas that are covered in the works are today part of the Water NSW Schedule 1 Restricted Areas. These accounts, coupled with Macqueen’s intimate knowledge of the terrain, provide a tangible sense of the challenges Barrallier faced, often in landscapes deemed “awful” to traverse.

Summary & recommendation

In conclusion, “The Frenchman” is far more than just a biography. It’s a meticulously researched and engagingly written account that illuminates a crucial period in Australian history. Andy Macqueen’s deep understanding of the landscape, combined with his historical and ethical rigour, makes this book an indispensable read for anyone interested in:

- Australian History: Gaining insight into the early colonial period and the motivations behind exploration.

- Colonial Politics: Understanding the strategic maneuvering and hidden agendas that shaped early expeditions.

- Aboriginal-European Interactions: Learning about the complexities of first contact, the reliance on Aboriginal knowledge, and the nuances of intergroup relations from an early European perspective.

- Blue Mountains Bushwalking History: Discovering the paths less travelled to places with familiar names, appreciating the challenges faced by early explorers, and connecting with the Ensign Barrallier Walk on a deeper level.

I wholeheartedly recommend this book to anyone keen to delve into a fascinating chapter of Australian history and appreciate the enduring legacy etched into the stunning landscape of the Blue Mountains. You can buy Andy Macqueen’s book at independent bookshops and via his website.

Further research

- Read the revised translation of Barrallier’s expedition by Milena Bellini-Sheppard (French with English translation)

- Watch Andy’s presentation to Bushwalking NSW on YouTube.

- Andy’s book, ‘Back from the Brink‘ is one of my favourites and brings to life the happenings and history of the Grose Valley Wilderness. Can you believe they tried to build a train line down beside the Grose River?!!

- Cambage’s account on the 1802 expedition (Trove)