Part 2 : From Clubs to the Future

Read Part 1 of the History of Bushwalking here.

The Detractors

But not all was sunny days and picnic sing-a-longs. For many conservative parts of society, the immense interest in the Mystery Hikes were not seen as a healthy pursuit of active outdoors life.

From the growing number of car owners, to ‘traditional’ club bushwalkers, to cultural conservatives and certain religious authorities, many viewed enthusiasm for hiking (especially by women) as examples of steep moral decline and the negative impact of an increased Americanisation of Australia. For them, all things good and upright were from Britain.

The arguments from conservatives and the responses from hikers often filled the columns of newspapers, however according to Melissa Harper,

“…the most dominant argument made in support of the hikes, and perhaps a suggestion that young Australians had not abandoned spirituality, was that in the bush, surrounded by nature and away from the artificiality of modern city living, they could feel closer to God.”

Melissa Harper, “Ways of the Bushwalker” (UNSW Press)

Even with all the enthusiasm and passion of the 1932 Mystery Hikes, the fervour didn’t last for more than a year. What it did do was help cement the idea of hiking into the recreational mindset of Australians and opened up the possibilities of walking in the outdoors to more people than at any other time. In the 1930’s it was considered fashionable and modern.

The Bushwalker Emerges

It seems strange to consider it today, but up until around 1927, the words ‘bushwalker’ and ‘bushwalking’, weren’t in common usage.

Sure, there are examples of “bush+walking” in early journals and writings, but it became more commonplace after the formation of the Sydney Bush Walkers Club (SBW) in 1927.

Interestingly enough, SBW had it’s origins in the (invitation only) Mountain Trails Club (1914), started by legendary bushwalker and environmentalist, Myles Dunphy.

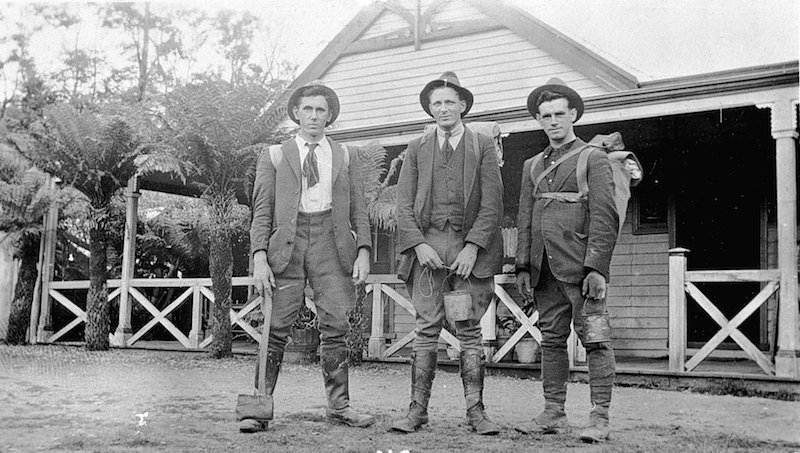

Myles and his mates Herb Gallop and Roy Rudder believed that their particular manly craft of ‘trailing’ and ‘tracking’, through trackless and tough terrain, self reliant (including hunting with shotgun), was an altogether new sport.

To them, their experiences couldn’t be more different than what the tourist walkers were enjoying in the mountain resorts. Theirs was active work, as opposed to the tourist’s leisurely stroll. Oh, and although the thought of admitting women in the club had been discussed, it was short lived.

It was from the desire of women to be involved in equally interesting and challenging walks, in untracked terrain, (albeit ‘easier’) that SBW was born.

But a war of words emerged in 1930s NSW where, in certain circles, to be called a ‘hiker’, or to say that you went, ‘hiking’ had negative connotations.

The Sydney Bush Walkers club took a stand against the rising use of the term ‘hikers’ or ‘hiking’ to describe what their club did and who they were. They saw that hikers were not ‘real’ bushwalkers, but some sort of frivolous, inexperienced creation, forged at the smelter of mass market tourism and hysteria that the Mystery Hikes had created.

“The efficient recreational walker, who knows how to camp as well as walk, is with us a ‘bushwalker’ not a ‘hiker’. It is hikers who go out and get lost; it is bushwalkers who rescue them. It is hikers who leave their fires alight often causing bushfires, or despoil the landscape by leaving papers, tins and orange peels about – The hiker is the muddling inefficient; the bushwalker is the expert.”

Sydney Bush Walker Magazine, January 1937

Excerpts like this from their club magazine, point to an arrogance and elitism of the time, sadly than recognising that there are many different and equally valid ways to walk in nature.

Not all bushwalkers agreed with their negativity, with some seeing the public interest in the Mystery Hikes as a positive thing. They saw that encouraging people to get out and walk in the outdoors (whether that be on formed road or tourist track), could only be a good thing for the acceptance and credibility of all forms of walking.

The Response

This exclusive attitude and the growing distrust of anyone not deemed a ‘real bushwalker’, along with a fear that the bush would be overrun with hikers, had several outcomes. It saw many clubs introduce entry criteria or ‘test walks’, where prospective members needed to prove not only their physical capability over several overnight trips, but they needed to demonstrate that they were socially compatible.

Additionally, clubs began to close ranks around the details and reports of their trips, choosing to keep their walks secret. This shut down the grand tradition held by the Explorers, Adventurers, Romantics and Thinkers, (as discussed in part 1) who wrote about their trips and published them in the mainstream press.

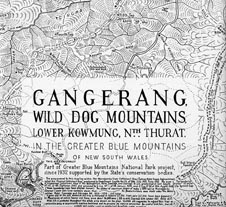

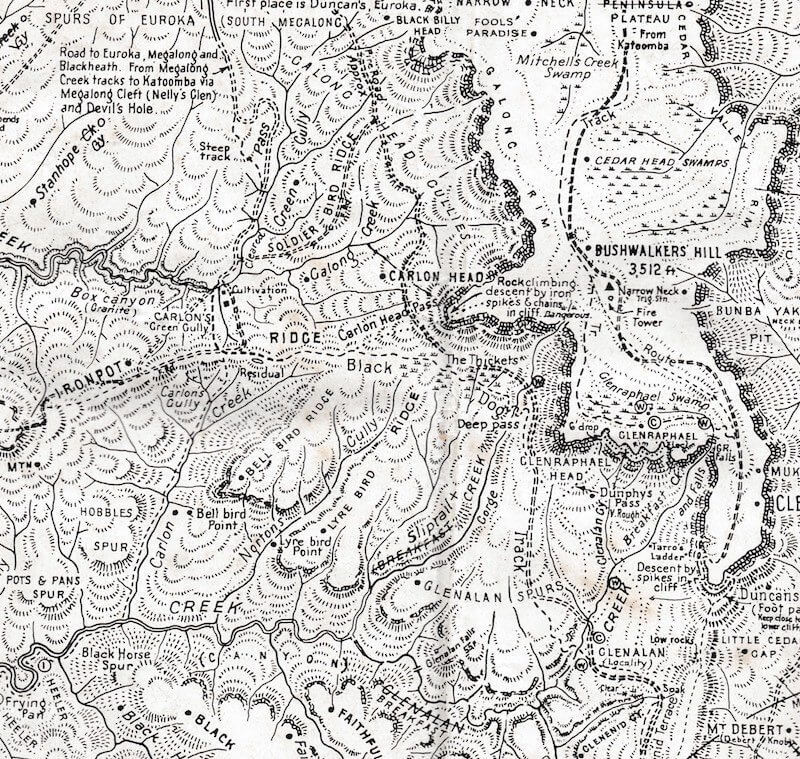

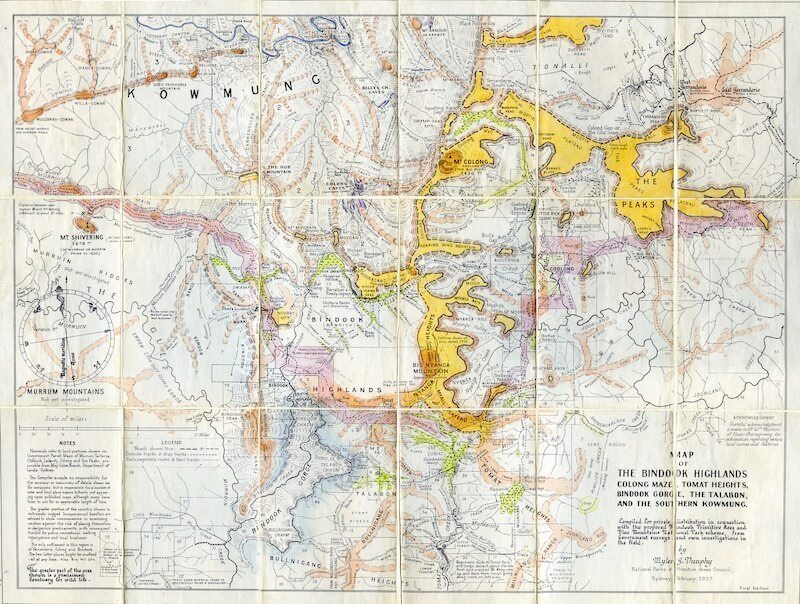

Rather than publishing first hand accounts, clubs were becoming prolific map-makers, creating hand-drawn works of art, that held topographic details to areas they visited. The Dunphy maps and other sketch maps, like those produced by the Coast and Mountain Walkers Club, are a good example of this.

This practice of sharing (or not sharing) continues today, with many who choose not to give details of their secret spots on the internet, whether it be to protect Wilderness areas from too many visitors, or to protect people without the necessary skills and experience needed to visit these places safely.

Although the strict new criteria led to the creation of more clubs by people who didn’t make the cut (eg. Coast and Mountain Walkers and The Bush Club), Melissa Harper suggests that amongst other external forces like the rise in car ownership, clubs started to experience a steady decline from the 1950s.

The Accessories

Up until the early 1900s, unless you were a swagman (ie. an itinerant farm worker), the people who ventured away from city life for walks invariably looked more like they’d just left the gentlemen’s club or were heading to church. No doubt, this was influenced by the English country ramble, which was considered a most acceptable past time in the Motherland.

Equipment

But as more people took to the bush, we developed a style of dress and accessories that were more suited to Australian conditions and borrowed from the humble “swaggie.” With a rolled blanket, wrapped in canvas, strapped to their backs and billy-can in hand, the walkers of the early twentieth century filled their repurposed farm sacks and chaff bags with food.

When Paddy Pallin started to create his ‘Paddy-made’ line of tents and packs in 1930, he commercialised the home-spun, DIY approach that many bushwalkers were experimenting with and that ultra lightweight walkers continue to tinker with today.

From the swag came the Army-inspired canvas rucksack, with multiple outside pockets, then the external A-frame, followed by the H-frame. Just as there was an evolution in bushwalking, so too the evolution of equipment had begun and continues to this day.

With current designs, the ability to have a good night’s sleep anywhere is now available. There’s now no need to cut a pile of bracken fern and kip down with newspaper, as some were known to do in the early days.

As more people buy more gear, there’s a concern that people will expect their gear (as seen in glossy outdoor retail ads) to get them out of trouble, rather than building their outdoor experience through many days on the track.

Food

Although there was experimentation in backpacks for trips, it appears that the diet of the bushwalker didn’t sway too far from their English heritage. Bread, potatoes, tinned meat, eggs, oatmeal, flour, butter, tea, rice, chops and bacon kept the protein and carb levels high, along with the weight of their packs.

The introduction of commercially available dehydrated food in the 1940s, (with reports of dubious taste, nutrition and gastrointestinal effects) helped make things lighter. Walkers also started experimenting with drying their own food.

Clothes

The hangover of the gentrified culture of walking in nature, took some time to evaporate. Some men were still known to wear heavy woollen suits and ties, with women in long skirts well into the 1930’s and 40’s.

But whether it was an example of the practical, no-nonsense attitude of bushwalkers or them relishing their place as eccentrics in society, they adapted fairly quickly to a uniform of khaki shorts, often with long socks as early shin protection. For ladies, this often meant wearing men’s clothes.

It was not uncommon for women to cache their feminine city clothes in the bushes on their way to a weekend adventure, only to collect them in time for the train journey home, once again returning to acceptable attire.

These days, rather than blending in with the bush like our khaki forebears, it’s more common to find bright colours and high tech fabrics. Undoubtedly safer, it’s a demonstration of how the growing awareness of risk, safety and responsibility changed the industry… not to mention fashion!

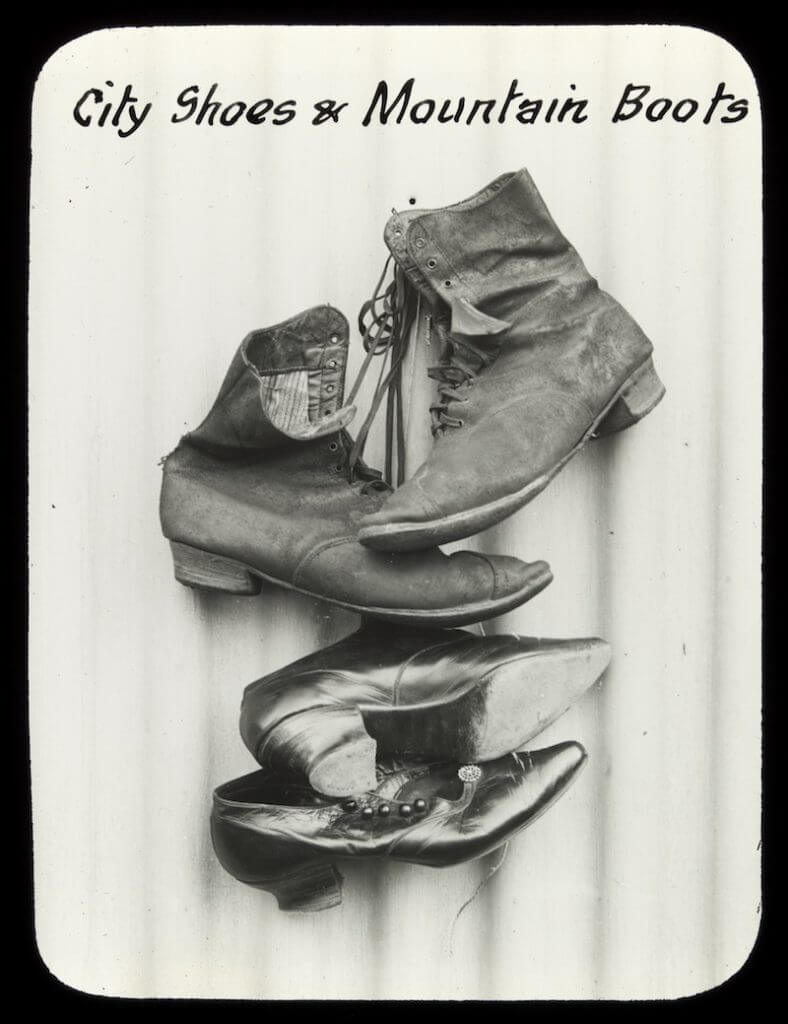

Footwear

With no such thing as hiking boots in the early days, our ever adaptable heroes of the day generally opted for heavy leather boots, nailing in their own hobnails. Some were known to wear sand shoes, with the trusty Australian made Dunlop Volley entering production in 1939. There is still a niche group of Volley (or KT-26) wearers, still leaving their recognisable footprints in the bush today.

Technology

A true standout of early bushwalkers, was their reliance on traditional forms of navigation. Not only were map and compass skills essential, but it was a given that walkers developed an understanding of stars and the movement of the sun, long before the days of GPS, Personal Locator Beacons (PLBs), navigation apps or even decent topographic maps. These hardy types were drawing the first maps as they went.

The Conservationists

One of the single biggest shifts along the evolution of bushwalking began in the 1930’s, however it wasn’t the formation of clubs.

It was the stepping away from the colonial concept that wilderness was a place that needed conquering or subduing to be of any value, to the awakening and understanding, that the value of wilderness, was in its very existence.

This awareness, that the Australian bush was in itself a thing of beauty, helped us to stop comparing ourselves with England’s manicured landscapes and developing an identity for ourselves, that reflected our environment.

In 1931, when a group of Sydney Bush Walkers and Mountain Trails Club members came across a local farmer proposing a walnut farm in the Blue Gum Forest, near Blackheath, plans were drawn up to mount one of Australia’s first environmental campaigns. It’s the stuff of legend, but demonstrated that with organised effort and a joint voice, the future of wild places can be preserved from development.

It is in this climate that Myles Dunphy rose to become one of the key figures in wilderness conservation in New South Wales. Through his National Parks and Primitive Areas Council, the forerunner to todays Colong Foundation for Wilderness, he (and many others) campaigned relentlessly for many places today that we take for granted, such as the Blue Mountains National Park and Kosciuszko National Park.

Never the shrinking violet, Dunphy’s elitist approach that only experienced ‘real bushwalkers’ should enter Wilderness, wasn’t always met with broad appeal. There were other strong voices of the time, like Marie Byles (Australia’s first female solicitor) who’s more balanced view expressed that the values of Wilderness were so great, that more than just the bushwalking elite should be able to enjoy them.

By clubs keeping places secret and restricting entry, they were not only limiting the number of people who joined their ranks, but also limiting the numbers of people able to enter what many of them saw, as ‘their’ wilderness. With exploration still high on the agenda for the ‘true’ bushwalker, they wanted to retain the possibility of wonder and discovery for years to come.

The Supported

As the peace loving 60’s passed and 70’s emerged, the idea of conservation gained more mainstream acceptance amongst Australians and once again, people seeking connections with natural places started to grow.

With cheaper air travel and the opening up of exotic overseas destinations like Nepal, the foundations were laid for companies (like Australian Himalayan Expeditions, who later became World Expeditions) to manage local tour guides and package up adventurous, expedition-like holidays for all.

To people outside of bushwalking clubs, these tour companies were the solution to the common desire we all hold for adventure and wonder.

In Tasmania, Craclair (now called Tasmanian Expeditions and also owned by World Expeditions) stepped up to local demand and in 1968 offered the first commercially guided experiences on the Overland Track, as well as rafting the Franklin River.

Non-club walkers and people with less experience, now had the ability to access and live amongst wild, natural places, where penny-saving club and independent walkers, had gone for years.

With walker numbers on the rise for Australian tracks, along with the number of operators servicing the demand increasing, the introduction of permit systems and quotas on popular tracks was introduced to control and monitor impacts, as well as provide much needed finances to maintain these tracks and fund related environmental projects. The best known of these was the Overland Track, which introduced controls in 2005.

Commercial guiding companies now form part of a multi-million dollar tourism industry, making it easier for anyone to have an experience on remote, long distance tracks in Australia. From the Larapinta Trail in the Northern Territory, to the Bibbulmun Track in WA; Great Ocean Walk in Victoria and even the Six Foot Track in NSW, all previously the domain of only the highly organised and experienced independent or club walker, are now open to all at a price.

The Future

From the very beginning, freedom from the stressors of urban life has been the key driver for most people wanting to go bushwalking.

Freedom to step away from the concrete and walk into the adventure of the unknown. To marvel at how simple living can be under the stars with a level of self-sustainability to match your comfort and experience. To see nature play out around you, not behind the glass of an exhibit. To be part of nature and connect with it in ways that are meaningful to you, whilst leaving no trace behind.

Today’s bushwalkers have learnt from the mistakes of our history. No longer is it acceptable to bash, burn and bury our rubbish, or carry a shotgun to shoot native wildlife for our food. Our challenge is to continue to learn and share the messages of minimal impact bushwalking and look after the precious places we’ve all grown to love.

Although these days, it may be one supported by safety nets of insurance, risk assessments, technology and controls unheard of in Dunphy’s day, one thing remains: regardless of whether you are an independent walker, a club walker or one supported by commercial operators, you are (and have always been), a bushwalker.

A version of this article by Caro Ryan first appeared in Great Walks Magazine.